This Week in Space 193 Transcript

Please be advised this transcript is AI-generated and may not be word for word. Time codes refer to the approximate times in the ad-supported version of the show.

Tariq Malik [00:00:00]:

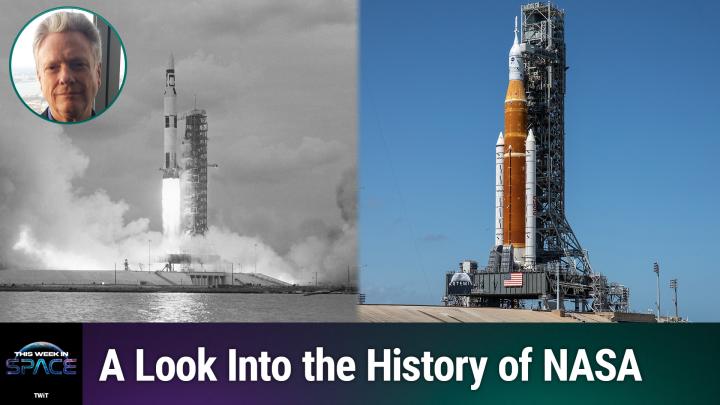

Coming up on this week in Space, NASA's first ever medical evacuation of the International Space Station is a success. Artemis 2 is finally rolling out to the launch pad. And if you've ever wondered how we chronicle the space age, well, we got former NASA chief historian Roger Launius to come tell the tale. Tune in. You won't want to miss it.

Rod Pyle [00:00:27]:

This is this Week in space, episode number 193, recorded on January 16, 2026: A History of Tomorrow. Hello, and welcome to yet another episode of this Week in Space, the History of Tomorrow edition.

Tariq Malik [00:00:42]:

Tomorrow, Tomorrow.

Rod Pyle [00:00:44]:

I'm Rod Pyle, editor in chief, Badass magazine, and I'm here with the man in the can, tarek malikofspace.com. hello.

Tariq Malik [00:00:51]:

Hello, Rod. Hello, space people. Happy birthday, Yasmine, to my sister. It's her birthday today. Yay.

Rod Pyle [00:00:56]:

Wow. Keep overdriving that mic, man. We're right there with you. This week, we're gonna be chatting with Roger Launius, Dr. Roger Laun, the former chief historian at NASA Headquarters and former Associate Director of Collections and Curation at the Smithsonian Institution. So this guy knows his space history. Actually, he knows a whole lot of stuff, but he really, really, really knows his space history. So this is.

Rod Pyle [00:01:19]:

This is going to be a fun one.

Leo Laporte [00:01:20]:

Yeah.

Rod Pyle [00:01:20]:

Before we get there, though, please don't forget to do us a solid. Make sure to, like, subscribe. And the other things you could do to support podcasts on your favorite podcaster, actually, go to all of them. Give us good reviews on Apple, Google.

Tariq Malik [00:01:35]:

He said support podcast. Support our podcast.

Leo Laporte [00:01:38]:

Our podcast.

Rod Pyle [00:01:39]:

I thought I said your favorite podcast. But, yeah, whatever you could do to make sure that people like us, we're getting good ratings, but we can always use more. And now a space joke.

Tariq Malik [00:01:50]:

I'm ready.

Rod Pyle [00:01:52]:

Hey, Tarik.

Tariq Malik [00:01:53]:

Yes, Rod?

Rod Pyle [00:01:54]:

What did Voyager sing on its way to Jupiter's moons? I don't know what I o, I o. It's off to work I go.

Tariq Malik [00:02:03]:

I love it. I love it. That's a good one.

Rod Pyle [00:02:06]:

Did we do that before?

Tariq Malik [00:02:08]:

I don't think so. By the way, you ever.

Tariq Malik [00:02:12]:

You ever watch that Sean Connery movie where he's like a sheriff?

Rod Pyle [00:02:15]:

Outland.

Tariq Malik [00:02:16]:

Yeah, yeah, Outland. Yeah, it's a very good one. Recently. Underrated. Underrated.

Rod Pyle [00:02:19]:

Very underrated. Although it is interesting. Their idea of high tech is green monochrome monitors on curved screens that are shaped like TVs from the 50s. But that's okay. And by the way, joke was mine.

Tariq Malik [00:02:33]:

That Was yours.

Rod Pyle [00:02:33]:

I made that up.

Tariq Malik [00:02:34]:

I love it.

Rod Pyle [00:02:36]:

Now, however, I've heard that some people want to use us.

Tariq Malik [00:02:40]:

Oh no.

Rod Pyle [00:02:41]:

I've heard that some people want to use us as drill bits into Europa's ice crest. When it's joke time in this show that was tortured. But you can help by sending us your best, worst or most of different space joke at Twist Twit tv. And we will read it on, on the air, online, on streaming and thank you vociferously for it because you didn't have to hear one of my space jokes.

Rod Pyle [00:03:04]:

And now it's time to go to headline news.

Tariq Malik [00:03:10]:

Headline news. Oh, I think it was early that.

Rod Pyle [00:03:13]:

Night so I heard something about some kind of crew coming back from the International Space Station for some reason.

Tariq Malik [00:03:23]:

You think you might have heard something about that?

Rod Pyle [00:03:25]:

I think. And you know what really bums me out is I was in Houston this week because I was on a panel there for a screening and you know, the 12 night span of time that I leave California, we get the first in easily a decade reentry over California, streaking from horizon to horizon across the sky and I had to miss it and I am so bummed.

Tariq Malik [00:03:49]:

Oh man, the video is pretty cool. We actually got some of that video on the site today and it's pretty.

Rod Pyle [00:03:55]:

Exciting to see the site being space.com.

Tariq Malik [00:03:57]:

Space.Com like it's the only site that anyone needs to think about, right?

Rod Pyle [00:04:00]:

Oh God. I believe there's called this week in tech. Yeah, tv.

Tariq Malik [00:04:06]:

So yeah, this was the week, my friends. The first ever medical evacuation from the International Space Station is complete. NASA astronauts Mike Fink, Xena Cardman and Japanese astronaut Kamiya Yui and Russian cosmonaut Oleg Platinov returned to Earth with a pretty smooth and fairly nominal splashdown on their crew. Dragon Endeavor spacecraft, SpaceX and their recovery teams with NASA were there within the hour, as they typically are. I mean it was from start to finish a very kind of run of the mill return to splashdown. With the only exception that they came back home a month early because of some sort of undisclosed medical issue with one of the four astronauts. We're probably not ever going to know if exactly what went wrong and with who, but we know that it was serious enough for them to come home, but not serious enough to drop everything and come home the same day. So it's somewhere in the middle there afterward, you know, Jared Isaac being NASA administrator, said that the crew member that was affected was fine, in good shape, you know, basically and doing well.

Tariq Malik [00:05:16]:

And all four of them went to a hospital in San Diego for the day on Thursday, the day before, they were recording this podcast for medical, medical checks and, and treatment, etc. Before coming home. They should be arriving at the, the Johnson Space center as we're speaking and recording this podcast today. So, so that's done the latest in a string of, of kind of space issues of different countries recently. But, but that's finished and in the can. And now we know what happens if someone has to come home quickly from the space station run and they, they.

Rod Pyle [00:05:51]:

Still haven't told us what the problem was or who it was with. I think I did shoot you a message. I was looking at some video feed from it and it did look to me. And of course it's low res, so it's hard to tell. It looked like one of the astronauts had an IV feed coming out of the sleeve of their spacesuit, but it's almost impossible to tell. But that did see that dangling around as they were getting ready to reenter. All right, Artemis 2 rollout. Yeah.

Tariq Malik [00:06:16]:

Yes, finally.

Rod Pyle [00:06:17]:

Yay.

Tariq Malik [00:06:18]:

Tomorrow. Tomorrow. As we're recording this today is. As we're recording this January 16th. On January 17th, NASA is finally ready to roll out their second mega rocket with Artemis 2. And we've got our own writer, Josh Dinner. Hey, Josh, if you're listening to this down at the Kennedy Space center, for this, it should take, you know, about eight to 10 hours for the Space Launch System to roll out to launch pad 39 beam at the Kennedy Space Center. NASA will have live coverage with live video, usually for the start, but hopefully they'll have it for the time.

Tariq Malik [00:06:55]:

I'm not sure. And, and this is it, you know, hopefully it's really, really, finally going to get to the moon with this mission and these astronauts. So there's a. But it's, it's going to be really tight. The first window for this mission is February 6th through the 10th, which is, as we're recording this podcast, like, less than three weeks away. And NASA says that they're not going to do a fueling test of the rocket until February 2nd. That does not leave a lot of time run at all, especially if you assume that something might go wrong either in buckling the rocket down, getting all of its systems all linked up, doing diagnostic testing. While they've launched this rocket and Orion before, when they did this back in 2022, it was uncrewed, and it was a very different Orion and a different sls.

Tariq Malik [00:07:46]:

They've made some tweaks to avoid those pesky leaks that we were talking about before the show Rod. And so now it's time to see if all of those things work. The crew is going to be out there. Reed Wiseman, Christina Cook, Vic Glover and Jeremy Hansen. They're going to be out there to do like a soup to nuts inspection and familiarization and probably a dress rehearsal again on the pad. And all of that has to happen in the next three weeks. And there just doesn't seem like a lot of time if one little thing looks like it's out of family or, or you know, sideways to be able to make that window. But NASA had a press conference today and they seem like they're committ and they, they were very annoyed and took issue when folks were asking if they were rushing for that window.

Rod Pyle [00:08:34]:

Yeah, I guess that makes sense. And our last story. One Ringy dinghy. Two Ringy dinghy. Maven, can you hear me? Are we going to get Maven back?

Tariq Malik [00:08:43]:

Yeah. Today is the first day that NASA has to try to reestablish contact with the Maven spacecraft around Mars. Our Eagle listeners might recall that back in December NASA lost contact with the Maven spacecraft, the Orbiter. This is an atmospheric studying spacecraft to kind of find out where Mars water went and, and to understand the volatiles. That's what the V stands for in Maven went over time from Mars. But it's been at Mars for quite some time. It's in an extended mission and it fell silent when it went around the backside of Mars and was out of communication with the, with the Earth. That was a while ago back in December.

Tariq Malik [00:09:27]:

Now here we are in January. The Mars has come out of solar conjunction which means that it was behind the sun as viewed from, from the Earth. And, and so now we can get signals to and from Mars regularly and the hope is that they'll be able to wake this, this up. Now Space news reports that the scientists just, they're not very optimistic about the chances right now because they were trying in December. They're going to try again and give it the, you know, the old college best. But it's, it seems like this spacecraft might be down for the count.

Rod Pyle [00:09:59]:

Do they think it's still tumbling?

Tariq Malik [00:10:02]:

Well, it was, it is, it was before and there's no cause to think that things could have changed themselves. Now if they get a signal that says hey, I woke up and, and I was all out of source and I fixed myself that that would be one thing. I think though that if they would have gotten that quickly because it only takes like what a half an hour for, for round trip signals right now between us and Mars.

Rod Pyle [00:10:23]:

Right.

Tariq Malik [00:10:23]:

They would have said something by now. And so it is still early days. This is the first day NASA typically tries for two weeks and that before either admitting defeat or making a final call to decide. And it's had a good life. I remember being there when Maven entered orbit around Mars with Jim Green, friend of the show.

Rod Pyle [00:10:44]:

Yeah, I wonder when a spacecraft is tumbling. I suppose it depends on the period of the rotation, but I wonder how much time, because, you know, the, the signal will come into phase and then you'll have it fat and then it'll go out of phase or out of. Out of contact. I wonder how much time you need to get enough data up there to tell it to arrest the tumble, if indeed it can.

Tariq Malik [00:11:09]:

Yeah. And that, that assumes that it's in a fashion, in a state where it's actually either ready to accept or send a signal. If it suffered like a hard fail, it could just be a hunk of junk FL in space right now and we wouldn't know.

Rod Pyle [00:11:23]:

So shades of Viking one that's still, still waiting on the surface of Mars with this little nuclear battery waiting for that last signal from Earth, telling it what to do that will never come.

Tariq Malik [00:11:37]:

Was I a good lander? No. Viking, when I'm told you were the best.

Rod Pyle [00:11:41]:

We're not going to talk to you anymore. All right. We'll be back with Dr. Roger Lanius in just a few minutes. So stay with us.

Leo Laporte [00:11:48]:

Hey, space guys. This episode of this Week in Space. I've always wanted to call you. That is brought to you by my mattress. You notice I'm a little chipper today. I had a great night's sleep on my Helix Sleep mattress. How are you preparing for the colder season? Are you spending more time indoors? Well, now would be a perfect time to invest in a new mattress so you can stay comfortable inside, relaxed on your Helix mattress. No more night sweats, no back pain, no motion transfer.

Leo Laporte [00:12:16]:

Don't settle for a mattress made with questionable materials. Rest assured that your Helix mattress is assembled, packaged and shipped from Arizona within days of placing your order. Yeah, they build it when you order it so it's fresh. You can also take the Helix Sleep quiz. We did this. It will match you with the perfect mattress based on your personal preferences and sleep needs. Fill it out, find out, then get the right mattress. Helix did a sleep study with Wesper that came out amazing.

Leo Laporte [00:12:46]:

And I have to say my experience confirms it. Helix measured the sleep performance of participants after switching from their old ma to a Helix mattress. Here's what they found. 82% of participants saw, almost all of them saw an increase in their deep sleep cycle. That's the sleep that really matters, right? Participants on average achieved 25 more minutes of deep sleep per night. That's exactly what I've experienced. Participants on average achieved 39 more minutes of overall sleep per night. You're going to feel better the next day.

Leo Laporte [00:13:13]:

Time and time again, Helix Sleep remains the most awarded mattress brand, tested and reviewed by experts. Forbes loves them. Wired loves them. I love them. Helix delivers your mattress right to your door. Free shipping in the US and rest easy with seamless returns and exchanges. The Happy with Helix guarantee provides a risk free customer first experience. They're really serious about that.

Leo Laporte [00:13:35]:

Ensuring you're completely satisfied with your new Mattress. Go to helixsleep.com.space for 27% off site wide during the Flash sale Best of Web exclusive for listeners of This Week in Sspace. That's helixsleep.com/space for 27% off the flash sale Best of Web now this offer ends January 21st, so make sure you enter our show name after checkout so they know we sent you. And if you're listening after the sale ends, you gotta still check them out. The deals are always great at helixsleep.com/space and if you support this Week in Space, you'll want to use that special address so they know you saw it here. helixsleep.com/space all right, Space Force, back to you.

Rod Pyle [00:14:18]:

And we are back with Dr. Roger Launius. So I've got a whole paragraph here for credits. Former NASA chief Historian, senior Curator and Associate Director for Collections and Curatorial affairs at the Smithsonian. He was on the worked with the Columbia Accident Investigation Board, fellow of a number of distinguished organizations such as aiaa, AAAS and others that are too many to list here. Recipient of multiple NASA awards, accommodations, and most importantly, perhaps writer of blurbs for some of my favorite books of the questionably emerging space. Author like me so much. Thanks for that.

Rod Pyle [00:14:58]:

And when you're, I don't know, what is your next book going to be? Number 35. Where are you now?

Dr. Roger Launius [00:15:03]:

Yeah, I lost count. It doesn't really matter anymore.

Rod Pyle [00:15:06]:

I think I counted like 22. So you're ahead of me. But hey, if you ever need a blurb from a B list author, I'm here.

Leo Laporte [00:15:12]:

Here for you.

Tariq Malik [00:15:13]:

Oh, we could all achieve such heights, you know.

Dr. Roger Launius [00:15:15]:

So.

Rod Pyle [00:15:16]:

Exactly.

Tariq Malik [00:15:16]:

So jealous. I've only got one in one of my belt. So.

Rod Pyle [00:15:20]:

So Tarek has a question that he needs to ask you, and then I'll, then I'll move on to mine.

Tariq Malik [00:15:25]:

Yeah. You know, thank you, Roger, for. And it's great to talk to you again. I think the last time we spoke was when I was still a writer at space. But, you know, one of the questions I like to ask everybody is kind of like their path to space. You know, how, how they, they, they, they've, they found that bug. If it's something that, that grabbed you when you were a kid or was it something as has happened that, that, that you found either in university or in your adulthood to find that path to, to space that has led to the career that you've had?

Dr. Roger Launius [00:15:59]:

Yeah, well, I mean, my, my career path was sort of an accident, but my interest in space goes back a long time. When I was a kid in the 1960s, we were following Mercury, Gemini, Apollo programs. I was old enough to read, just to watch those first moon landings and, and I also learned that as a kid I could write a letter to NASA and they would send me stuff.

Rod Pyle [00:16:22]:

Oh, yeah, I never even thought to do that. Yeah.

Dr. Roger Launius [00:16:26]:

Mission patches, you know, you name that kind of stuff. And I, and I figured out that there were multiple centers and if I wrote to the difference, they would send me different things.

Rod Pyle [00:16:37]:

Oh, you're clever.

Dr. Roger Launius [00:16:39]:

Oh, my goodness, I wish I still had that stuff. But, but be that as it may, I. I was excited by it when I was, when I was a kid growing up in the 60s and early 70s. But, you know, I sort of went away from it for a while and didn't pursue it in graduate school. It wasn't my primary. Interesting. And then when I finished my PhD, I went looking for a job and found one. Working for the Air Force, not, not space, but, but airplanes was pretty cool, too.

Dr. Roger Launius [00:17:09]:

And, and then I made a transition to NASA in 1990 after I had been working for the Air Force for a number of years. Wow. And that sort of set me on the path to do space history.

Rod Pyle [00:17:20]:

So I guess one thing I've always tried to get my head around, ever since I learned there were such things as chief historians for both headquarters and NASA field centers. What's a day in the life of a NASA chief historian?

Dr. Roger Launius [00:17:33]:

Like, you know, it's. I mean, the NASA history program does essentially three things. The first thing is to collect documentation about the history of the agency. The second is to preserve that and make it available. And the third piece of this is to, is to disseminate knowledge about this effort. And so the first part of that is mostly about archival activities. And the headquarters office that I was responsible for had an archivist there and some contract people who did work for us along those lines. And there was a constant effort to collect materials.

Dr. Roger Launius [00:18:16]:

The dissemination came in a variety of forms. The preservation, of course, was a big piece of this. We want to make sure that it's available for future generations. But the dissemination of it can take all kinds of forms. Historically, the NASA history program has been built around publications, in a very real sense, books and articles and things of this nature. When I got there in 1990, within a very short period of time, we started to see the digital age emerge and the placement of information online. And NASA got very heavily involved in that very early on, trying to maintain websites and data centers that were accessible by people remotely that we got involved in as well in terms of the NASA history program. So the dissemination took a form beyond the printed word to ones that were electronic and online.

Tariq Malik [00:19:18]:

And you were NASA's chief historian, am I correct? Until about. Is it 2002? 2001?

Dr. Roger Launius [00:19:25]:

Is that 2002? I was there for 12 years, yeah.

Tariq Malik [00:19:28]:

And then you transitioned over to the Smithsonian. Was there culture shock between going between, I guess the history makers to the history archivists kind of thing there, or is it more like an adventure where you get to mess around with all this stuff?

Dr. Roger Launius [00:19:42]:

Well, I mean, So I spent 12 years in NASA headquarters and that's probably long enough for a person to sit in the same job. At least that's how I felt at the time. And so when I was called by the folks at the National Air and Space Museum, would you be interested? They said, and maybe they caught me on a little bit of a bad day. And it was a pretty easy process to say, yeah, I'm interested. That's a cool opportunity there as well. And in terms of talking to a broad audience, there's none broader than what you see at the Smithsonian with literally millions of visitors a year.

Rod Pyle [00:20:20]:

So I've got a two part question that may have some thorns in it. We'll see. There's a lot of talk, and I'm guilty of it myself, of us coming into a second space age. You know, you and I grew up during the first space age. I think we're almost the same age. And now arguably we're in a second, very different space age. So I think my question is, how do you feel about that in broad terms? Is that a proper classification? And then I want to talk about public attitudes towards both space ages, if that's what we decide.

Dr. Roger Launius [00:20:54]:

Yeah. Well, I mean the space age came and it hasn't gone away. So in terms of a second space age, I'm not sure I accept the terminology. I think there's been a transition in the type of space activities that's taken place and we've really seen it, you know, since the beginning of the 21st century with the rise of commercial actors in ways that they hadn't been present before. Although that, that's a sticky wicket too. It's hard to kind of make sense what is a commercial actor versus one that is a non commercial actor? And clearly if it's a government entity, we know it's not commercial. But you know, Boeing, which is a representation of sort of very early space activities, is a commercial entity. And oh, by the way, NASA and people who do space things are not its largest customer by any stretch of the imagination.

Dr. Roger Launius [00:21:50]:

So we have to be careful about that. But that this, this sort of transition that we're seeing today, where NASA is not necessarily the only game in town, has, has made some, some significant differences. And I think we'll see those further as, as time passes.

Rod Pyle [00:22:13]:

John, do you want to go to break early? Because I'm going to ask a fairly lengthy question. Okay, we're going to swing to a quick break and we'll be right back. Go nowhere.

Leo Laporte [00:22:21]:

I'm back. Sorry, sorry, Rod and Tariq. But This Week in Space is brought to you by Melissa. And I really wanted to tell you about these guys. The trusted data equality expert since 1985. For a long time, forward thinking businesses are using AI these days in all kinds of new ways. But AI, as you know, is only as good as the data you feed it. You can have the most sophisticated AI tools in the world, but if your customer data is incomplete or duplicated or just plain wrong, you're training your AI to make expensive mistakes.

Leo Laporte [00:22:54]:

That's where Melissa comes in. They are more than address validation people. They're Data scientists. For 40 years Melissa has been the data quality partner that helps businesses get their data clean, complete and current. Now here's what Melissa does for you. First, they've got global address verification and autocomplete. This is great. In your shopping carts, anywhere your customers interaction with you or even for customer service reps.

Leo Laporte [00:23:19]:

You get real time validation for addresses anywhere in the world. That's important. You want your deliveries to actually arrive right and your customer experience to start strong. They also do a very important to reduce fraud, mobile identity verification. You connect customers to their mobile numbers which reduces fraud. It lets you reach people on the devices they actually use. So it's better for customer service too. They also do change of address tracking, automatically updating records when customers move so you don't lose revenue due to outdated information.

Leo Laporte [00:23:49]:

They also solve a problem everybody has with address lists deduplication. They do smart deduplication it turns out, and this makes sense. On average, a database contains 8 to 10% duplicate records. I think mine's 50%. Melissa's powerful matchup technology can identify non exact matching duplicate records. So they don't even have to be perfect matches. They can sense duplication. They will also do something really cool, data enrichment.

Leo Laporte [00:24:14]:

Which means they can append demographic data, property information and geographic insights to take those basic contact records and turn them into marketing gold. The new Melissa Alert service monitors and automatically updates your customer data for moves, address risk changes, property transactions, hazard risks and more. Whether you're a small business just getting started or an enterprise managing millions of records, Melissa scales with you. They've got easy to use apps for all the tools you're already using. Salesforce Dynamics, CRM, Shopify, Stripe, Microsoft Office, Google Docs and more. And of course, Melissa's APIs integrate seamlessly into your existing workflows or custom builds. Melissa's solutions and services are GDPR and CCPA compliant. They're ISO 27001 certified.

Leo Laporte [00:25:00]:

They meet SOC2 and HIPAA high trust standards for information security management. Clean data leads to better marketing, ROI, higher customer lifetime value and AI that works as intended. Get started today with 1000 records clean for free at melissa.com/twit. That's melissa.com/twit thank you Melissa. You've been a great partner over the years. Great to have you in 2026 and thank you space guys. Now back to Rod and Tariq.

Rod Pyle [00:25:31]:

Roger One thing that's always interested me about having existed during the space race, I remember what public sentiment was like broadly as much as I understood it as a younger man. But one thing I push back on, because I don't think it's correct, is you will broadly hear people, many whom should know better, who are our age, talking about the golden age of Apollo and the public was behind it and the nation was united and all that. And I've looked at every polar poll I can find from then till now, and it's different polling agencies asking different questions of a different population. But in really broad terms it hasn't changed that much that I could see. You know, there's spikes during Apollo 8 and Apollo 11 and the shuttle accidents and so forth, but overall it's kind of the same now as it was then. Which, depending on which question you ask, isn't great. If you say should America be a leader in space? 60, 65% of the people say yes. If you say should America immediately go back to the moon no matter what the cost or however you phrase the question, it's more like 17%.

Rod Pyle [00:26:34]:

What are your observations on that?

Dr. Roger Launius [00:26:36]:

Well, that's absolutely right. I mean there is this kind of rose colored glasses looking back on that past of the 1960s and the exciting, what I refer to as the heroic age of space flight. Mercury, Gemini and Apollo. Time frames in which the astronauts were much more household names than they are today. And every launch was viewed as newsworthy and was covered ad infinitum by the news organizations. So that there was a different vibe to it. There's no doubt about that. And when we look back on it, we all think of it as this great success story and how we were all supportive of it.

Dr. Roger Launius [00:27:20]:

That's not true. It just simply is not true. There was attacks on the NASA budget every year in Congress, both from the political left and the political right. So on the political right they thought it was a waste of money and we should put it into something else like military or give it as a tax cut back to the American people. On the political left, people attacked it based upon the desire to expend more resources on social programs of various types. That money could be spent elsewhere more effectively, they said. And that was the case throughout the 1960s. And those are the politicos that's the high end people, the general public.

Tariq Malik [00:28:08]:

They.

Dr. Roger Launius [00:28:09]:

Didn'T dislike what NASA was doing. And in fact, if you ask a poll question to somebody, to a community of people and ask do you like NASA? You got an overwhelmingly positive response. But you know, if you ask the question do you like what NASA spends on space versus what we would spend on. Name the program of your choice. NASA almost always loses. And, and at no time does more than 50% of the public say that they think going to the moon is a good idea. With the exception of the summer of 1969 when we landed there for the first time. When Apollo 11 went there.

Dr. Roger Launius [00:28:47]:

Yeah, for, for a short period of time in the summer of 1969, there's more people than not who thought it was a great thing to do.

Tariq Malik [00:28:55]:

See that.

Dr. Roger Launius [00:28:56]:

But that's, I mean that's just the nature of this and, and polling is, has its flaws, but it is empirical data and we have to address that.

Tariq Malik [00:29:07]:

See, that's why I feel redeemed because here we are like 57 years later and we're getting ready to go to the moon again. And it seems like we're in that same situation. You know, one of the things that has really come up that we've been following@space.com Roger, is this whole billing. And I think maybe Rod was alluding to this too earlier about that we're locked in like another space race. I mean, that was a big driving factor of that first trip to the moon back in 69. And it is a selling point at least now on the hill for NASA's Artemis push to get astronauts back to the moon again. And I'm just curious from that perspective of watching that as a kid and then pursuing history as a profession, if you feel that the comparisons, it's like apples or oranges, or is it just like a 2.0 of that initial race with a digital twist that we see today?

Dr. Roger Launius [00:30:11]:

Yeah, well, it's not the same. I mean, and this is something I've tried to explain to students and of course, not having lived through any of it, they have no background. I mean, we had a peer competitor in the 19, well after World War II, into the end of the Cold War in about 1990, where the confrontation was on a broad front. Sometimes it was military, not always, and sometimes it was these surrogates like the space race, to demonstrate technological prowess, scientific and technological prowess. And this was a struggle over who was going to control the future of the world. Was it going to be democratic and capitalistic or was it going to be authoritarian and command economy? And the Americans won that, no question about it. And that was a remarkable outcome. But the demonstration, better than just about anything you could think of in the 1960s, was the space race in which nobody died, at least not intentionally.

Dr. Roger Launius [00:31:26]:

And if you're sitting on the sidelines looking at these two competitors and you're a non aligned nation and both sides are vying for your support, throw in with us, you know, the Americans and the European west or the Soviets and their allies, you're going to want to go with the side that you think is going to win. And no better demonstration of who is going to win than was in science and technology. And that's why the Apollo race to the moon was such a significant factor in the Cold War. And I would contend it was really significant in ways we haven't appreciated. We don't have anything like that today. There's nothing out there like that. There's no competition between nation states over this in any, in any real serious manner. And there's no existential crisis in which we think we could get nuked.

Dr. Roger Launius [00:32:27]:

Maybe we should be a little more worried about that than we are. But the reality is we don't have the same situation at all today.

Rod Pyle [00:32:35]:

So one of the things, and I know you weren't the NASA media department, so don't get me wrong here, but I am curious from, from your perspective as a historian and really a storyteller at core in a lot of ways, you know, it seems like it's been very hard for NASA to sell its message since the beginning, and it's not really part of their charter, as I understand it. But, you know, this is an incredible agency. It's one of the top five brands globally for the last 30 years running, at least the accounts that I could find. But it does seem, you know, we've seen Spin off magazine, we've seen various publications. People like Tarek and I do our best to tell the story because we're so compelled by it. But it seems like it's been a real challenge for the agency to tell its story well. Do you have any thoughts on that?

Dr. Roger Launius [00:33:21]:

Well, you know, I think NASA's actually done a reasonably good job at telling its story, and it does have a mandate to do so because one of the statements in the NASA charter, the Space act of 1958, is to disseminate broadly what they are doing. And relatively speaking, they've done okay with that. It's hard to keep people's attention, and that's we are and we always have been at some level, sort of attention, short attention span people. And so whatever's new and whatever sort of looks exciting, we sort of rush there and we pay attention to that for a very short period of time until something else overtakes it. And day in and day out, NASA does great things, but they're not always newsworthy all the time. And so people pause and pay attention to a particularly spectacular space mission with astronauts on it, or they, they pay attention when there's an encounter. Pick the mission of your choice, New Horizons to Pluto, for instance. It could be any number of things, and people pay attention when those things happen.

Dr. Roger Launius [00:34:37]:

But there's lots of periods in which there's not a lot of newsworthy activities. And most people then, if they're just casual observers of this, sort of lose track of these things.

Rod Pyle [00:34:53]:

I think that's very well said. Well, let's take our short attention spans and focus them on a break for just a few moments, and we'll be right back. So stand by.

Leo Laporte [00:34:58]:

Hey everybody, Leo Laporte here. It's your last chance. We're in the final stretch of our 2026 audience survey. So important for us both to know you better because we don't gather information about you except this one time a year. And it helps us with advertising and we collect no personal information. We just want to know about you in general. So if you would help us out. If you haven't filled out our survey yet, this is the time it closes January 31st. twit.tv/survey26.

Leo Laporte [00:35:32]:

It helps us improve our shows and it helps us make money and we need to do both.

Leo Laporte [00:35:37]:

So survey is at twit.tv/survey26. Should only take a few minutes. Thanks in advance.

Tariq Malik [00:35:44]:

It's really interesting the way that you put that about attention spans because I had thought that the shift into I guess what is now a digital media landscape that we all find ourselves in. Of course that Space.com I'm partial because it's a dot com that that the access to, to. To the information would be a lot easier for the people to be able to follow the space history makers of their choice. Now when I started, for example, I used to have to request Betamax tapes for space shuttle missions. And now you get it live through like the ether. It seems like an astronauts sharing photos straight from space. And I'm just curious how you see that revolution in media reach, I suppose. Personal reach, transforming the public's awareness of what space programs around the world are doing.

Dr. Roger Launius [00:36:39]:

Yeah, no, I think that that's absolutely what happens. We, there's so much that's available to us. I mean so much information on all kinds of subjects. Anything you could can think of is out there. And they all have their audiences. And the result of that is there's a segmentation of those audiences. Not everybody can do everything 24 7. And so what we find I think is that we don't have the same sort of.

Dr. Roger Launius [00:37:14]:

When I was a kid growing up, my parents turned to CBS Evening News everybody night and they saw Walter Cronkite for, you know, for a half hour, half hour news program. And that was their news for the day. Might look at the newspaper in the morning but, but that was it. And everybody saw those newscasts. And so if there was a, if there was a space story, everybody knew about it. The market is so fragmented. You can, you can say that's good or you can say it's bad and probably a little of both. But the reality of that is it people send self select are they interested in space? Then they're going to pay a lot of attention to what's taking place in space.

Dr. Roger Launius [00:37:57]:

And if they're interested in, you know, name the name the billionaire of your choice who's interested in sorts of activities and they want to know about that. They can track that on a minute by minute basis almost.

Tariq Malik [00:38:09]:

Yeah.

Dr. Roger Launius [00:38:10]:

And people do, but that's going to be a much smaller percentage of the public than even is interested in, like the space effort as a whole. And I think our world today is sort of built around how many times have we done this? Information is at our fingertips in ways it never was. I can remember as a historian before the digital age, in which, you know, Friday afternoon about 5 o' clock or so, I get a call from somebody. Can you tell me who the first man fly in space was? And I know that off the top of my head, but usually I would say something to the effect, okay, which way did you bet and what's my cut? The bar where you guys are sitting talking about this now, none of that happens because you just look it up.

Rod Pyle [00:39:04]:

Yeah, yeah.

Dr. Roger Launius [00:39:05]:

And there before you in ways that you never thought of before. So it's available at our fingertips and anybody wishes it can find it very, very quickly. Now, that says nothing about the plethora of sites that are out there, some of which may be just screwball sites, and the discerning nature that one has to undertake and the critical nature you have to have to bring to the use of those things. But they're there.

Rod Pyle [00:39:38]:

And is it interesting that, I mean, when you and I started writing books, you did so well before me, but we still had to go to libraries and pull out drawers with a thousand cards in them that were three feet long and all that. Isn't it interesting that as this has become more democratized and information is more freely available, that the number of people that believe that the moon landings never happened has increased, which is a real head scratcher to me.

Dr. Roger Launius [00:40:02]:

Well, so the first thing I. The first question I would ask is, do we really think it's increased? I'm not sure that that's the case.

Rod Pyle [00:40:09]:

Well, and it's interesting you say that because there was that recent.

Tariq Malik [00:40:12]:

It wasn't Kim Kardashian.

Rod Pyle [00:40:15]:

No, no, no. There was a. There was a survey, the first, supposedly the first international survey of attitudes about space travel on the moon. It was really broad. It wasn't Isesco. I can't remember who did it, but, you know, that was their claim. But we don't really have data that I know of to any extent before that. So you may be right, but it does feel like, you know, when people start turning to Steph Curry and the Kardashians for truthful facts about history, I begin to worry.

Tariq Malik [00:40:47]:

The NASA administrator had to tweet back at her to say, yes, we landed on the moon. Yes. God.

Dr. Roger Launius [00:40:53]:

Well, okay, so, I mean, you always see these things in movies and whatnot about not landing on the moon, and usually it's done as sort of an inside joke in some form or another, and yuck, yuck, that's all fine. How many people actually believe that we didn't, though? And unless there's a concerted effort to try to understand this from the standpoint of public polling or whatever, I don't know how you're going to make sense of that. Yeah, there's anecdotes that are out there of people who say we didn't, and there's, you know, Mythbusters and all kinds of other groups that have gone on and debunked all of that sort of thing.

Rod Pyle [00:41:35]:

But.

Dr. Roger Launius [00:41:36]:

But the reality is that the. The only polls I've seen date from, like, 2010. And it's. It's like, you know, 5, 6, 7% who say, I believe we did not land on the moon. Now, I find that a little troubling, too, but 5, 6, 7% is sort of the. The margin for error for a lot of polls. So it's.

Rod Pyle [00:42:03]:

Was. Was that a domestic poll?

Dr. Roger Launius [00:42:05]:

That was domestic.

Rod Pyle [00:42:06]:

That was domestic. Okay. So the one I'm talking about was, I think, 2019. I'll have to look it up, and maybe I'll drop you an email. But I think US was, you know, it was divided up by age categories. And of course, the, you know, 18 to 32 or whatever that category was, was the highest, saying, oh, I don't think we did. It was maybe in the high teens, but Russia was something like 72%, which was a shocker. But I guess if you include everybody out in Siberia in the hitter lands, that makes sense.

Rod Pyle [00:42:36]:

But the UK was 52%. What happened to our allies?

Dr. Roger Launius [00:42:44]:

So, so, so here's a fine point. Do they say, I, we did not land on the moon, or did they say, I question whether or not we landed on the moon? Those are two different things.

Rod Pyle [00:42:56]:

I didn't actually read the questions, phrasing. So that's a good point. See, that's why you had that big job, and Tarek and I are nibbling around the edges.

Dr. Roger Launius [00:43:06]:

It just. I, you know, I think. I think there's obviously, especially among younger people who didn't experience it. More questioning of it because they didn't experience it. And that's fair enough. But there's a difference between I question whether or not this happened versus we just didn't do it, period. It's not true.

Rod Pyle [00:43:30]:

And I will add to a young person now who has seen, especially with AI but even just in the last 20, 30 years, who has seen reality mimicked so well with Digital Graphics and CGI versus. Do you remember when the Apollo 12 camera failed, did you ever switch to NBC for their simulation of the moonwalk?

Dr. Roger Launius [00:43:50]:

I might have. I don't recall. But, yeah, I know what you're talking about.

Rod Pyle [00:43:53]:

So CBS was using, you know, pilots dressed up in spacesuits up at Grumman. ABC was using a soundstage in Hollywood. NBC was using marionettes on a little moon set made out of dusty glasses, but it looked like Thunderbirds or go, if you remember the show. And I just thought, oh, my Lord. So having seen that, I was pretty sure they weren't faking it. But I digress. I think Tarek has a more compelling question. John, do you want to do the break first or go now? Okay, we're going to swing.

Rod Pyle [00:44:23]:

We're going to simulate our way into a break, and we'll be right back. So stand by.

Tariq Malik [00:44:27]:

You know, Roger, one of the things that I was thinking about as we were preparing for today is kind of how the weight of space history falls on this part of the year. Roger or Rod mentioned the work that you had done with the Columbia Accident Investigation Board. Of course, that tragic shuttle accident was on February of 2003, and we're coming up on the 40th anniversary of the Challenger accident as well, and the Apollo 1 fire in 67. And I'm wondering from, you know, your, your professional kind of perch, how important the, the chronicling of those accidents investigations and their subsequent, I guess, responses on, on, on the NASA side really play in just the ongoing effort to remain vigilant for spaceflight safety and whatnot. You know, like how important those, those from the accidents themselves to the investigations and then the learnings play on a regular basis. You know, when, when you were a chief historian and then I guess now from the outside watching the evolution for this new push to the moon.

Dr. Roger Launius [00:45:39]:

Yeah, well, I mean, the, the accidents, and it's not just the ones in which lives were lost, such as those, but yeah, all of the mishaps that have taken place that were not in which nobody died all play a part into, in the NASA process to try to understand the technology what went wrong with it, how to correct it, how to ensure that there's no additional accidents in which people die. And so maintaining that knowledge and that base of information is a key part of what all of the operations at NASA are engaged in. And I would assume the same is true at any of the organizations that fly rockets into space, at SpaceX or wherever else it happens to be. This is a hard thing to do. And the technology, I referred to it as angry technology. And you can like or not like that particular term, but I refer to it that way because it is so potentially deadly. And you just have to maintain your edge on this the whole, whole time. I mean, we're all familiar with, with car accidents and things of this nature, and, and some of those are tragic and some people lose their lives in the process, but the vast majority of those accidents are fender benders in which nobody's hurt you.

Dr. Roger Launius [00:47:06]:

You have an accident in a spacecraft, it could, it could easily turn into one in which people lose their lives. And that's one of those, those things in which no amount of safety is, safety awareness is sufficient to ensure the, the rigor that, that you undertake these activities. And it doesn't matter where you are, who you're flying, what country it is, private sector or whatever, it's, it's the same everywhere. Yeah.

Rod Pyle [00:47:34]:

So I've spent not as much time as I would have liked to, but over the years, sometime National Archives, JPLs, Johnson Space Centers, Kennedy and so forth. And when I think of that experience vis a vis what you did from the top perch as the historian for headquarters, were there times where it got. This is a two part question, so bear with me where it got frustrating trying to capture, you know, you're trying to get your arms around tons, literally of paperwork and records to preserve these histories. So that must have been hard enough. But then at least with an organization like JPL, which is the only place I saw it in any detail, as you move into the 21st century, suddenly there's a lot less paperwork generated and a whole lot of this history is going to be digital in ways that you can't really preserve. And I had to actually have people go back and kind of convert their digital history into print for the book I was working on. So A, how difficult was it to get your arms around the whole picture in your job? And B, was there a transition there that was challenging.

Dr. Roger Launius [00:48:43]:

It's always been a challenge. I mean, we're talking about records here at this point. And so historians basically live and die by paper records, documentation that's created the closest to the center as possible. You know, a person's recollections written down in real time, made available to somebody to use to try to tell the story of what's taking place. And we've always had this problem. It's always been there. And a huge change took place in the first part. Well, actually the last part of the 19th century in which telephones started to be used and you did not have then a written documentation of a telephone call.

Dr. Roger Launius [00:49:34]:

Usually, I mean, sometimes somebody would sit down after the fact and say, okay, this is what we talked about. This person said this and I said that, and they would have a document that they created. But most of the time you had that ephemera that didn't get. Didn't get kept in the same way. So historians had to try to deal with that. And we developed approaches that journalists are well familiar with, which is calling up people and talking to them about it, recording, recording their responses. We call them oral histories, you all call them interviews. They're the same thing, really.

Dr. Roger Launius [00:50:13]:

And that's one way to try to get a handle on that documentation. The. But in the digital age, we've got the similar sort of problems associated with this. And now everything's. I shouldn't say everything, but an awful lot of things are done through email or text or various things like that in which there's not necessarily a permanent record except an electronic one. And we have tried, and we did this at NASA when I was there, to try to work with the various program offices to, you know, maintain that kind of materials for knowledge capture as programs unfold. And some did it well, some did it less well, all tried, but it's a difficult task, no doubt about it. And we've also sort of lived and died on the capability.

Dr. Roger Launius [00:51:01]:

Every retiree I've ever run into at NASA or positions I've worked for has got boxes of stuff ends up in their garage or their basement at some point. And they're usually happy to let you have that stuff at some point down the road, well after the fact. And since historians don't look at things in a time sensitive way, in the same way maybe a journalist does, if it takes 20 years for that material to find its way into collections, we can live with that. We'd like to have it sooner. But it works out okay the way it is.

Tariq Malik [00:51:41]:

They don't worry about how do you. How do you document a tweet, Rod? Right, like the. All of that stuff, what do we do? What if, what if they change and they shut that whole company down. And then all that stuff is such.

Rod Pyle [00:51:52]:

A thing as screen captures.

Tariq Malik [00:51:53]:

Yeah.

Rod Pyle [00:51:54]:

You got another question, by the way.

Dr. Roger Launius [00:51:57]:

Can I just respond to that? How many trees tweets really need to be captured? That's one of the.

Rod Pyle [00:52:06]:

If they're from Elon Musk, they're all meaningful. Oh, wait a minute. I got, I got confused.

Tariq Malik [00:52:10]:

Well, I think about Massimino.

Rod Pyle [00:52:12]:

Right?

Tariq Malik [00:52:12]:

Mike Massimino.

Rod Pyle [00:52:13]:

Yeah.

Tariq Malik [00:52:13]:

The first person ever to tweet from space.

Dr. Roger Launius [00:52:16]:

You would want, by the way, social media has been a boon along these lines, especially as some of the people who've been engaged in, you know, in space have done a lot of things to sort of communicate with the public. And, and that is a very valuable process. Not just, not just for publicity purposes either for them and for NASA as a whole. But, but in the context of the historical record.

Tariq Malik [00:52:42]:

Yeah. And that's going to be. That's going to be continuing along with Artemis 3 on the moon. That first tweet from the moon. That's going to be history. Right. First Instagram breaking news. That first photo of Pluto on Instagram.

Rod Pyle [00:52:55]:

Well, right. And so as long as you bring that up. Tarek, didn't you have one more question about social space in the age of social media?

Tariq Malik [00:53:03]:

No, I think we talked about that earlier about the relevancy and the attention span we were talking about there. I mean, I've always thought that NASA needed a fan club. And then 2007 they got it with the advent of Twitter. And I had to have JPL's media team explain what Twitter was to me.

Dr. Roger Launius [00:53:20]:

I'm so ashamed.

Rod Pyle [00:53:22]:

So, Roger, I guess my last question here is when is book 127 coming out? What's it going to be about?

Dr. Roger Launius [00:53:31]:

Well, I'm not going to be writing it. Maybe you will.

Rod Pyle [00:53:36]:

Do you have anything in the works, though?

Dr. Roger Launius [00:53:38]:

Yeah. So basically I'm working on a project right now that's. And you've seen these books in other. In other settings. It's basically NASA history and 100 objects and it'll be. It's a fun book.

Tariq Malik [00:53:52]:

Oh, that's cool.

Dr. Roger Launius [00:53:54]:

And it's got all the kinds of stuff you would think of and maybe some things you won't think of, but trying to tell that NASA story, and not just NASA, but the NACA before it as well, going back to 1915 and using 100 objects to sort of talk about the broad based associations of the agency over time and the kinds of activities it's engaged in. And, and we're in the process now. Of putting that together. I've been looking at page proofs and, and we're still a long way from having this done, but it's, it's underway.

Rod Pyle [00:54:33]:

And who's publishing that?

Dr. Roger Launius [00:54:34]:

It's going to be done by Smithsonian Books.

Rod Pyle [00:54:37]:

Okay. I kind of figured you have to.

Tariq Malik [00:54:39]:

Let us know when, when that, when that comes out that we'll want to definitely revisit and.

Rod Pyle [00:54:43]:

Yeah, yeah, we'd love to have you back on because I think we got through about two thirds of our questions, as usually happens. Well, I want to thank everybody, especially you, Roger, for joining us for episode number 193 that we like to call A History of Tomorrow. Roger, where's the best place for us to keep up with what you're doing and your accomplishments?

Dr. Roger Launius [00:55:04]:

Heck, I don't know. I'm not on social media.

Tariq Malik [00:55:09]:

Dickens Pearl clutching.

Dr. Roger Launius [00:55:12]:

You know, I am, I am actually retired, although I do book projects and things of this nature. I'm, I just abandoned my social media connections. I do things like this when I'm invited and I've done a few of those things in the last few months and so you can see me there.

Rod Pyle [00:55:35]:

All right, well, now that we're over our intimidation and inviting you, we'll, we'll, we'll do some more often because this is a great session. Tarek, where can we find you pursuing your various venal things these days?

Tariq Malik [00:55:46]:

Well, you can find me at space.com, as always, this weekend, you'll find me watching with bated breath as NASA rolls out the Artemis 2 space launch system rocket to the launch pad at last. Huzzah. You know, so, so there is that. And, and then hopefully this is the, this is the month. Next month. You know, by this time next month, we'll have gone to the moon and back. It's going to be real tight like we talked about earlier, but it's going to be real, real tight. So we'll see.

Tariq Malik [00:56:14]:

We'll see.

Rod Pyle [00:56:14]:

Yeah. Well, whisper it to NASA.

Tariq Malik [00:56:16]:

Also on the, on all the social medias at @tariqjmalik. I forgot. And on YouTube @spacetronplays, so.

Rod Pyle [00:56:21]:

And check those hydrogen seals for fueling. And of course you can find me at pylebooks.com or at adastarmagazine.com. Remember to drop us a line at twis@twit.tv. We love to get your comments, ideas, suggestions, questions, space jokes, and we answer each and every letter. New podcast episodes publish every Friday and your favorite podcaster, so make sure to subscribe, tell your friends and give us reviews. Good ones, hopefully. And follow the TWiT Tech Podcast Network, at TWiT at Twitter and on Facebook and TWiTTV on Instagram. And that's all the social media I can think of at the moment. Thank you, Roger.

Rod Pyle [00:56:54]:

We really appreciate you coming on and thank you, everybody, and we'll see you next week.