This Week in Space 170 Transcript

Please be advised this transcript is AI-generated and may not be word for word. Time codes refer to the approximate times in the ad-supported version of the show.

0:00:00 - Tariq Malik

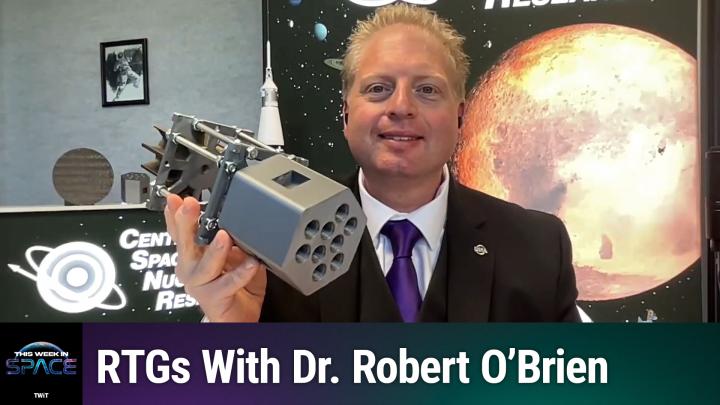

Coming up on this Week. In Space, the end of the universe is happening sooner than you might think. There's something happening on August 2nd, but it's not what you think, and Dr Robert O'Brien of the Center for Space Nuclear Research at USRA tells us what to think when it comes to RTG nuclear generators on NASA spacecraft. Check it out.

0:00:25 - Rod Pyle

This is this Week in Space, episode number 170, recorded on July 25th 2025: Atomic Space Batteries! Hello and welcome to another episode of this Week in Space, the Atomic Space Batteries edition. I love saying that I'm Rod Powell, editor-in-chief of Bad Aster Magazine. I'm joined by my fellow nuclear wannabe, Tariq Malek, editor-in-chief at space.com.

And today we have the good fortune of being rejoined by Dr Rob O'Brien, the Director of the University Space Research Association's Center for Space nuclear research. You know, I've always wanted the title something better than hey, you or bonehead or whatever, and that's a pretty cool title. I don't know if it'll ever fit on a lower third for television, but it's. It's a pretty cool title, I think. Before we, before we start, please don't forget to do a solid and make sure to like and subscribe and the other podcast and other viewing options things, whether it's on Youtube or, um, uh, apple podcast or google podcast, wherever it is you you access, us listening or watching or both, because, uh, we need the love and we we live and die by your support. So give us a thumbs up or a poke in the eye or whatever.

Now I have from Scott Ulrich, Scott modified space joke because I changed what he sent us. Hey, Tariq, yes, rod. Why did elon musk fall into a wormhole during his first flight on starship? Uh, I don't know. Uh, why? Because he failed the doge on time, on time. Oh, I get it, I get it. That took a bit. Okay, that's like that laugh was the laugh version of a golf clap. Now I've heard that some people want to stuff us into a black hole with this joke time of this show, but you can help send us your best, worst or most of the space joke at twisted twittv. I haven't gotten one for three weeks, come. Come on people. Shame on people not sending us their space jokes. And just an admonition you know, if you look up 101 funniest space jokes on the web, we've seen this already. We kind of need original stuff, or at least something in print, because that way it has been accessed a godjillion times. All right Onward to Headline.

0:02:47 - Tariq Malik

News, headline News.

0:02:50 - Rod Pyle

Headline News. Headline News You're like Jeff Jarvis on the other podcast, craig Craig, craig Newmark. Okay, from space.com. This may happen after I'm dead. Actually, I think they're all from space.com this week, except for the last two aren't. But the end is nigh in 33 billion years. So new discoveries in dark matter show that it may end up crunching the universe sooner than we thought. Yeah, so I'm going to start drawing down my 401k. What about you?

0:03:27 - Tariq Malik

yeah, yeah, you know it's time to go actually get that tattoo and do the skydiving, you know, to get, get all the bucket, those things checked. So no, this is, this is, and it's basically it's a new estimate for when the universe is going to die in the big crunch, you know. So we had the big bang, whatever there's a singular 13.7 billion years ago, explodes, creates everything and, like everyone around us. And scientists basically used new results from surveys by the Dark Energy Survey, the Dark Energy Spectroscopic Instrument, sorry, where they're tracking kind of the extent of dark energy. That's the force that we can't see, that we can't measure, but we can see, through indirect gravity effects, that it's accelerating the expansion of the universe so that everything is just flinging itself away. So when does all of that energy dissipate? When does it all go? So they have basically used all of those observations and this is, by the way we should point out, this is not a peer-reviewed piece of research and that means that scientists have not vetted the whole thing.

0:04:38 - Rod Pyle

Other scientists.

0:04:39 - Tariq Malik

Yeah, other scientists. This is a paper that came out in June that is just kind of getting some traction on Archive. That's a preprint server so it still has to be vetted to ensure that everything is copacetic. But they're saying that there's a new model of dark energy behavior that they can pull from these surveys that would suggest that that crunch, that end of the universe when it all kind of peters out, is going to happen a bit faster than we thought. So 33 billion years is the new expiration date for our universe. Uh, hopefully not hopefully that you know we'll find out that we're wrong, because that seems kind of sad to know that there's an end date, but uh, I mean, that's a long time from now, like completely I guess it's like downloading that app called death clock where it tells you how old you are when you're going to die.

0:05:27 - Rod Pyle

Mine said 76. So I decided to make some decisions. You know, science can be very depressing, and I have a. I have an idea. Are you ready? I'm ready. Let's just stop paying for science, and then these bad things won't happen. I don't know about that.

If you don't get climate change data, you don't have climate change as a problem. If they stop telling us that smoking is bad for you, it's okay. We'll go back to the days where the doctors used to do commercials saying I choose Chesterfields, all right. Enough of that, allsurferspace.com Nothing's happening. On August 2nd.

0:06:01 - Tariq Malik

Yeah, this is a fast one, but I just want to remind people that you may be seeing a lot of headlines that say that August 2nd, the whole world will go dark, and they're talking about a solar eclipse, except, the only hitch is that on August 2nd of 2025, there is no solar eclipse. Oops, in fact, in August 2nd of 2026, there also is no solar eclipse. Oops, in fact, there isn't a solar eclipse, a total solar eclipse, on August 2nd until 2027. And even then, the whole world will not go dark, just the part that's in the shadow of the moon. And yet this was like gaining traction all week, and so we had to weigh in to let everyone know that this August 2nd, which is a Sunday, I believe nothing untoward is going to happen.

0:06:48 - Rod Pyle

The, the, the sky is still going to be there except mars, will be four times the diameter of the full moon right I can, I know, I can guarantee that for half the world, the world will go dark because it will be night time.

0:06:59 - Tariq Malik

So there is that, but there is that but. But you know, we took it as an opportunity to let people know that on August 2nd of 2027, that's going to be the longest total solar eclipse in ages like this century, for sure so far, and so that is one to miss, not to miss. It's going to cross over Egypt. It's going to be really really great. Also, in September, there's a total lunar eclipse. That's going gonna be really really great. Also, in September, there's a total lunar eclipse that's gonna be really exciting, as well as a partial solar eclipse. But August 2nd 2025, nothing's happening.

0:07:33 - Rod Pyle

So if we go to Egypt, can we have our Raiders of the Lost Ark moment with a gem and a staff and, yeah, yeah, have that laser beam okay can you imagine what a, what a, what a circus it's going to be?

0:07:46 - Tariq Malik

Because it's going to happen over the pyramids and everything. It's a circus any time.

0:07:51 - Rod Pyle

So then it's going to be like sheer lunacy. That would be a cool place to see it, though.

0:07:55 - Tariq Malik

Sure lunacy or sheer. Oh yeah, it's like that's a moon pun, because it's the moon, right, I get it.

0:08:08 - Rod Pyle

I see what you're getting see, okay, moving on, uh, also from space.com mother earth 2. Oh yeah, 35 light years from earth, l98 59 is a cool, dim red dwarf star already known to host a compact system of small rocky planets. Um, sorry, that's the name of the planet, I think no, it has an f, the name of the star.

0:08:21 - Tariq Malik

It has the F. 9859 is the star.

0:08:24 - Rod Pyle

Planet F, all right.

0:08:27 - Tariq Malik

But so this is my grades in high school so-called Earth-like in the habitable zone.

0:08:32 - Rod Pyle

but because it's a red dwarf, the habitable zone is about 10 feet from the star, that's right. So its whole year is 23 days. Whole year is 23 days. They do note that it has low mass, which may indicate that it's got lots of water, but they need to investigate for an atmosphere and check for tidal locking. Now the other problem is red dwarfs aren't terribly stable in terms of radiation and so forth, so isn't this kind of a low probability for a place for critters?

0:09:01 - Tariq Malik

Well, you know, there was a time where they thought that it would be too inhospitable, but I think that that thinking has eased a bit because they're realizing that there's much more variation in what these conditions can be around the planets. Now this is technically a super earth it's 2.8 times the mass of earth, so it is bigger. It does move faster 23 days, like you said for their year but it really remains to be seen. A lot of the scholarship that I've read says yes, the radiation environment extremely high, extremely active around these red dwarfs. But I saw that BBC TV show way back when and that was hilarious. So I think that red dwarfs have a lot that they can give. Is that a different red dwarf? Well, and if?

0:09:47 - Rod Pyle

the planet is tidally locked. I mean, there's also a lot of discussion and disagreement about tidally locked worlds. If a planet is tidally locked and you're in a high radiation regime but you're around the Terminator, slightly on the dark side of it, where it stays like that all the time, that could be a whole nother story. Yeah, exactly, if you're under a rock outcropping, you can turn into a bigger amoeba or something. All right, and before we jump off of this NASA budget, what's happening with the NASA budget Tariq?

0:10:18 - Tariq Malik

I wish I knew. I know that you picked this space news story about the Senate folks, but I can't read it because it's behind a paywall and I missed it.

0:10:25 - Rod Pyle

However, however Well, but the Senate is pushing back, which is what we care about.

0:10:30 - Tariq Malik

The Senate, yeah, the Senate.

This has happened in a few different committees that we've been following, but the Senate as well as the House, I should point out have both flagged science missions that they're worried about in the current 2026 fiscal year budget request from the Trump administration, and they're saying no, we need to preserve this science, we need to do this, don't cancel this mission, et cetera.

And in fact, the Senate Appropriations Committee has actually flagged a bit of an increase of a budget for NASA compared to what we're seeing in the Trump administration's request.

Now, the Senate version and the House version both of them have been created, at least at the committee level. They still have to go all the way up through their levels and then they have to be reconciled right, and so there's still a long way to go to see if they're going to buck the administration's request for NASA science overall. I should point out that all of this comes on the heels of a Moon Day quote-unquote protest that dozens of NASA employees, contractors and their supporters staged outside the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum in Washington DC on July 20th, the anniversary of the Apollo 11 moon landing, really demanding some sort of attention from congressional leadership towards the science and the budgeting process, because they feel that all of these cuts are extremely damaging to both the science capabilities of NASA now and the future for years to come. Because people are leaving, either being forced out through layoffs, forced out through cuts, forced out through the, you know, deferred resignations that they're being pushed to take, and then they're gonna go somewhere else, somewhere like some other space agencies.

0:12:18 - Rod Pyle

Well, or to private industry, or to retirement, or to academia. At which point? So there's a last story from political space, but it was saying at least one in five NASA senior staff, mostly top scientists, engineers and senior managers have either left or plan to announce their departure by today, according to documents obtained, which brings us closer to 3,000, not 2,000. You know, the oldest guys aren't always the smartest ones in the room, but they are critical in terms of experience and the brain trust and so forth. So the damage may already be done a lot of it.

0:12:54 - Tariq Malik

We don't know if we can get these people back or not?

I mean, we talked about Lori Leshin leaving, you know, resigning from JPL, the cuts that were happening there and actually, just you know, since that political report that you cited, we actually found out that the director of the Goddard Space Flight Center also stepped down, mackenzie Lystrup. So this is still all very dynamic and happening right now. Meanwhile, these people that are on the ground floor that make the space agency work everyone from the scientists to the engineers to the administrative folks are saying that the agency is on fire and they need support from the government to put it out.

0:13:36 - Rod Pyle

Well, and you wonder at the rate that women in senior positions in the military are being pushed out. You got to wonder if there's that same paranoia at nasa of you know. I feel like you're walking with a target on your back. All right, before we we go on to dr rob o'brien, who's coming up in just a moment, we got a question, uh, yesterday from lisa z lisa who says I was just curious if either of you have the opportunity to go to the carmen line or the space station for free, would you go?

Elon musk could go to space, but he doesn't seem to want to. So I responded by saying yes, I thought we would, but in my case I'd rather do it on blue origins, new shepherd, if it's suborbital, than uh the uh, virgin galactic. Although I wouldn't turn either down, I just like the idea, because I'm old school, you know going up in a rocket and coming down, if it's to the space station, which would require a little more prep and weight loss and so forth. I would much prefer to go up on a Crew Dragon because, well, starliner on the one hand, and on the other hand, if you've ever seen what the inside of a Soho capsule looks like when there's three astronauts or cosmonauts in it, there's barely room to move your urine bottle.

0:14:48 - Tariq Malik

You're like in a fetal position, oh my.

0:14:50 - Rod Pyle

God. And then there's I don't know what are those packages that are like right up against their helmets.

0:14:55 - Tariq Malik

That's like the supplies and the gear and stuff.

0:14:58 - Rod Pyle

Okay, because they look like parachute packing, but you shouldn't put the parachutes inside the capsule.

0:15:02 - Tariq Malik

No, it's all the supplies, it's all crammed in there, but it's a real small capsule.

0:15:06 - Rod Pyle

Yeah, orbital module bigger on the shenzhou. That was informed that. Yeah, that's why the shenzhou's look so clean. It's lengthened, but but if you look at I did you. I don't think did you go to the um the dragon, the crew dragon, unveiling at spacex years ago no, you were the one that was there yeah, okay, I guess that's why I didn't see you there, because I was supposed to be doing it. Um, you know it wasn't fully kitted out yet, but it was like stepping into somebody's walk-in closet.

I've seen the mock-up that they had at Building 9. It's big.

0:15:36 - Tariq Malik

Yeah, it's large. I've also seen the mock-up at Building 9 of the Soyuz, but I didn't get to go inside because Miles O'Brien was filming a segment there and this is like in the early 2000s.

0:15:46 - Rod Pyle

What is the insider that you could say Building 9, like we're all supposed to know what that means.

0:15:50 - Tariq Malik

Building nine is the building at the Johnson Space Center that has all of the mock-ups in it and everything that the astronauts use, All right.

0:15:57 - Rod Pyle

Well, let's get on to the good stuff. We'll be right back after this short message with Rob O'Brien to talk about atomic space batteries Don't go anywhere. And we are back with Dr Robert O'Brien, who is the director of the Center for Space Nuclear Research for USRA. Thank you for joining us today.

0:16:14 - Dr. Robert O'Brien

Rob. Well, thanks for having me back.

0:16:16 - Rod Pyle

It's great to see you Well it's really fun to have you back. We had a great time last time. Could you give us just a refresher on USRA and your specific center?

0:16:28 - Dr. Robert O'Brien

Happy to yeah, so I am the Director of the Center for Space Nuclear Research. Happy to yeah, so I am the director of the Center for Space Nuclear Research. We're a center for excellence for nuclear propulsion and power for space and we have been in this field for about 20 years. This is our 20th year of operation and we've been really pushing the envelope and challenging the bounds of status quo, thinking outside the box, encouraging the next generation of nuclear scientists and engineers into the aerospace crossroads with nuclear energy for that 20-year period. And, yeah, we're doing a lot of fun thinking and development of technology and systems and strategy.

0:17:09 - Rod Pyle

Well, that is great, and, of course, today we're here to talk about RTGs, or radioisotopic thermoelectric generators. I think I got that right, which I first heard about, I think, when I was young, during the Apollo years, and I became aware of it because on the Apollo 12 landing was the first one where they had an RTG to power the ALSEP surface experiments and, of course, the camera burned out, so we weren't able to see this, we were just, basically it became a radio show once they lost their camera after the landing.

0:17:44 - Tariq Malik

Are we going to skip my question, rod? I know that we've had Rob on it, not yet, not yet, not yet.

0:17:50 - Rod Pyle

But there was kind of a Laurel and Hardy audio show between Pete Conrad and Al Bean while they were trying to get that fuel element out of the cask, to the point that Pete Conrad says get me the universal tool, which is a hammer, and starts beating on this cask with this radioactive core in it that they had to go put in the outset package. So that certainly got me interested once I realized that that was a chunk of, was it?

plutonium yeah, plutonium 238 fuel yeah absolutely generally, something you don't want to be hitting with a hammer. So that got me fascinated with RTGs. So they are a great way to power deep space probes anywhere from Mars and beyond, as Walt Disney used to say. But before we go forward with that, I believe my partner has a question for you.

0:18:37 - Tariq Malik

Yeah, I was like why are we jumping straight into it? You know there are people our listeners who might have missed Rob's first episode, so I just wanted to make sure that we gave them a chance to. And, by the way, we didn't say that USRA stands for University Space Research Association. So just for folks who don't know, that's the group. But, Rob, just a quick reminder. You talked about your expertise there at the center, but how did you fall into the space black hole, like Rod and I did? Just to give people that reminder, that refresher course.

0:19:10 - Dr. Robert O'Brien

Yeah, yeah, happy to go back on that. I think, like all of us, there's a lot of influence from what we watch. The environment that we live in, watch on TV, people around us, family they all inspire us to do things and find our passion area. I worked into the space arena purely from that childhood set of experiences in terms of what I watched on TV watching Star Wars movies, a little bit of Star Trek got boldly going, but I think that the things that we can do, it just seemed like there was an immense amount of energy quite literally involved in some of those old TV shows.

And then, when I started my professional career in space technology development, I transitioned to look at some of the technologies I think we're going to talk about today, but nuclear technologies in general as a focal area for my career, because there really is a huge challenge of how you power missions in space, how you propel missions in space, and doing that efficiently is challenging.

Solar power works to a degree, but sometimes there's a need for just more energy density, whether you're going into deep space or really difficult environments, if you're working in eclipse, in craters on the moon, and I was working in in development of systems at the University of Leicester in the UK for initially Arctic exploration and then to move on and deploy those technologies we develop here on earth for exploration of icy moons like Europa.

And I think some of the challenges there that I learned early on what was a bad thing was scope creep, where a mission wanted to go from one week to two weeks and then two years under ice or on another planet or on an icy moon. That's really challenging. You've got to take all that juice, all that energy to the surface, and it wasn't going to happen with lithium polymer batteries that we power most of our missions with today. And so I sort of moved on to look at nuclear energy and started scouring the chart of the nucleides back in 2006. And I kind of discovered that americium-241 was a European solution for powering missions in space Nice, and that's kind of a parallel to the US strategy, but I think it's starting to have its own gravity here stateside as well, so I'd love to chat more about that.

0:21:54 - Tariq Malik

So you heard that, rod, he said Star Trek in there and nuclear science, which means that he said some Star Trek. That means that Rob can tell us where the nuclear vessels are, I think.

0:22:05 - Rod Pyle

You were just waiting for that, weren't you? You were a little generous, Tariq, with comparing us to him. We said how he joins into space like we did. It's kind of different, you know, rob, can you hold up your PhD thesis for us to see this?

0:22:23 - Tariq Malik

is where we say he wrote the book. This is the difference between him and us. Yes, he wrote the book.

0:22:28 - Rod Pyle

My master's thesis was about a 16th of an inch thick and light reading at that. I chose my program because I did not have to write. A master's thesis was about a 16th of an inch thick and light reading at that.

0:22:33 - Tariq Malik

So I chose my program because I did not have to write a master's thesis.

0:22:36 - Rod Pyle

Well, there you go so I come from an era where um, because I'm I got 20 plus years on, you guys, maybe, maybe more than that in rob's case but I come from an era where I grew up seeing black and white saturday morning movies where the the tag was things like it's atomic and the atomic monster, and atomic spaceships to Pluto and that kind of thing. Everything was going to be atomic. Of course this was all fission, because you know how dangerous can fission be? It's no big deal, and we kind of found out that's not the case. But then come RTGs, which I guess were actually deployed terrestrially in the 50s, right, and then in space, starting in the 60s. But before we get too carried away with that now, I called this episode atomic space batteries. But these really aren't batteries, they're power generators. So if you could give us the layman's my Labrador can understand it explanation of what an RTG is and how it works, that would be great.

0:23:37 - Dr. Robert O'Brien

Absolutely happy to yeah. So an RTG stands for radioisotope thermoelectric generator, and in that name it suggests that what we're converting is thermal energy, heat to electrical power. Is thermal energy, heat to electrical power. And so the power conversion technologies, the converters, work using a physics phenomena called the Seebeck effect, where if you have a temperature differential between two materials, they can generate electricity. Electrical power can flow, and it's really a matter of engineering of those physics devices. So it's a cascade or an insulation system, with a cascade of these devices that convert the heat to electricity and the waste heat that passes through that material composite then radiates to space, then radiates to space. So we use a fin or a radiator panel, just like we would for rejecting heat from any other spacecraft, or even our cars, where we have radiators to reject the heat from the internal combustion engine. We have to waste some of that heat. So Carnot efficiency drives us. So at best we could convert around 60% of heat to power. In reality we're stuck around 30% thereabouts.

0:25:03 - Rod Pyle

And we'll be going through some of these missions. But just for people who have listened to the show before, we have talked a lot about Voyager. Voyager is working with rtgs and has been since its launch in the 70s late 70s, so that's how how long these things are effective. They do diminish over time and we'll talk about that later. But basically, as I understand what you just said, it's a a warm piece of of nuclear material surrounded by thermocouples that generate power as long as you let the heat flow through the bubble Exactly yeah.

0:25:34 - Dr. Robert O'Brien

So it's that nuclear decay that generates the heat, and there's some isotopes that are our favorites, our best choices from an engineering perspective. We want good, high power density, but there's also a big trade space. That's the type of radiation that isotopes make or produce. So you have to fight both heat generation and radiation damage. So there's lots of things that you have to think about. And then toxicity how you encapsulate materials. That's a serious consideration when we look at fabrication and launch safety. These are all really important areas that the engineering solution has to develop. But yeah, it's just that conversion of decay heat, of a radioisotope to electricity through thermoelectric. There are other methods as well to convert radiation to electricity and we can certainly talk in more detail about later, but that would be direct energy conversion, but with the name RTG, that's, the heat to electric conversion.

0:26:36 - Rod Pyle

Okay, Tariq, I know you're next, but go to a break, so standby, we'll be right back. Hold on to your atomic elements.

0:26:44 - Tariq Malik

You know, rod mentioned Voyager. I think that's probably for the layperson probably like the easiest example or the clearest example of where these types of systems you know had been used. But I was really surprised, just in when we were talking offline before the show started, that the use of these in space was, you know, much, much earlier. I mean, I think that it's kind of with the start of the space, space age, right. I mean like when was the first time we started using these in space? And was it, I guess, and why? Why did we choose that, I suppose, opposed to solar or something like that?

0:27:21 - Dr. Robert O'Brien

yeah, so I mean the first, the first use of rtgs, uh in the us, uh, and and public demonstration actually uh was under president Eisenhower, so we put a polonium 210 powered RTG on the president's desk in the White House. I think that's incredible.

0:27:41 - Tariq Malik

But it's a demonstration of trust and faith.

0:27:46 - Dr. Robert O'Brien

It's a little toxic and you know we endeavor not to expose anybody as we're engineering the materials, engineering the systems, and that's exactly why safety is every part of the consideration of the engineering solution. But we demonstrated that I think that shows trust in engineering and chemistry and physics that we could bring this to the highest office in government here in the US and I think that's an important milestone and from there we saw a lot of demonstrations. There's been around 44 missions flying RTGs or using RTGs over history 38 to 40 US RTG missions. I think that there's a long history there and pushing the envelope of what can be done in space. Like you say, it was since the dawn of the space age.

We wanted to do challenging things, go to challenging places and orbits that might eclipse significantly or have an extended period of time in darkness, and that's really hard to do with solar power, or you have to have a very large solar array and a significant amount of energy storage battery to power the mission itself. So I think that's the why is it's to go to the places that aren't easy, and you know there's a term that I've started using. You know it's mission enabling value and I think that's why we use RTGs and fission systems is because we can't do a mission without nuclear energy, and so if you've got mission enabling value, it offsets the cost of executing the mission with nuclear energy and really allows us to do the other things.

0:29:37 - Rod Pyle

So before we came on we were talking briefly about the first RTG powered satellite that I found, on the US side anyway, which was the US Navy's Transit 4A in 1961. And you said it created 1.7 watts of power is that right.

0:29:53 - Dr. Robert O'Brien

I think it was like 2.7 watts of electric. Yeah, it was pretty small.

0:29:58 - Rod Pyle

So was that actually running the satellite and the transmitter, or was it just a demonstration?

0:30:02 - Dr. Robert O'Brien

So that can be used to charge batteries and then from the batteries you can periodically discharge with burst power applications like radio transmission when you're over a ground station or collecting data using a sensor. So, yeah, nothing has changed to some of those use cases and as we look to the future, I think we're going to see more and more agile systems built with flexible use of power, not just peak power being the approach like we take today with flagship-type systems, but actually looking at energy storage hybridized with radioisotope systems.

0:30:41 - Rod Pyle

So I think generally people listening to this show are used to the idea of RTGs being used in deep solar system missions, because as you get further and further out, of course, there's less solar energy and the solar panel systems get immensely large. But one thing at least that I don't hear discussed a lot is, uh, the uses on Mars. So both Viking landers in 1976 had RTGs on them and could have lasted a lot longer than they did, but for various reasons they fell out of contact within a few years. I think the longest was before six years, and that was a Viking one in 1982. Um 1982. But the Voyagers are, of course, the classic example because they're still talking to us and they've been out there since 77 78. How many watts are they generating at this point? What percentage of original capacity was that?

0:31:33 - Dr. Robert O'Brien

yes, so you, you have an isotope as the fuel source, as plutonium-238, that has an 88-year half-life, and so you produce roughly half of that thermal power every 88 years. That's what we're looking at as a decay scheme. There are other material problems that start to arise with radiation damage. Neutron exposure, gamma exposure starts to degrade the thermoelectrics. But yeah, we've still got plenty of life left in the fuel, and certainly the degradation mechanisms happen over a long period of time.

0:32:15 - Tariq Malik

Can I interrupt? Does that mean that, even though we lost contact with like the Vikings, that the RTG is still like pumping out heat and stuff like that? Like, could we go Exactly, Tariq? Like plug stuff. I mean like that's so sad.

0:32:29 - Rod Pyle

Well, to your point, I was at JPL, I don't know, six years ago. I was talking about Viking to somebody in the hallway and an engineer walked out of one of the offices and he said you know, we're thinking about that again, right? I said what are you talking about? And he had actually worked up a study or a paper on the idea of sending a tremendously powerful radio signal towards the Viking 1 landing site to see if it would bounce off the surface and hit the dish. Because the whole reason we lost contact is the dish rotated off axis because of a bad command string and suddenly it couldn't see earth anymore and it went silent. So for all we know, it's sitting there waiting for its last message, like oh man what do I do now, daddy?

but, uh, that that didn't go anywhere, but that's not what we're here to talk about. So Galileo and Cassini were both also RTG powered, and then of course, the Curiosity and Perseverance Rovers are as well, and we had prior to that. Of course we had Spirit and Opportunity, which were solar panel powered. But as doesn't get discussed enough in public forums anyway, you know, when you have solar panels in space, that's one thing. When you have them on mars, they tend to get covered in dust and they're usually perpendicular to this or parallel to the surface, so they're flat and they they pick up a lot of dust. And you know there's been talks about having air blowers on them or vibrating mechanisms or something. It turns out there are enough wind storms that they generally get cleared off. But you know, it would seem that you'd want to power everything in space with RTGs, dragonfly, but there are problems with that, right.

0:34:07 - Dr. Robert O'Brien

Yes. So we want as much power as we can get. As a mission designer, you want to maximize the power budget that's available and you know that's not always as easy, especially with environmental conditions. So if we're turning attention to Mars specifically in this example, you know if we're looking at putting a human expedition to Mars in the next few years, we need lots of power for life support and even propellant manufacturing for Earth return. So if you're factoring in a solar plant to do all of that, you need to think about degradation due to wind, storms, dust deposition.

There are clever technologies like ultrasonics that can shake the dust loose, but you, you can't fix broken panels. Yeah, on mars you, you've got to have excess capacity. So let's say, for example, you need three megawatts of power to generate propellant to come home over a one to three month mission lifetime on the margin surface. With solar you really ought to put five megawatt plant there just in case you have a seasonal upset. You get weather systems that damage some of those generation sites. So with nuclear you can make it really compact and actually we've already started demonstrating the ability to make breathable oxygen on Mars and some of the precursors for liquid fuels like syngas. So, splitting the margin CO2 in the presence of water, you can make syngas, which is hydrogen and carbon monoxide, and they're building blocks to some really interesting chemistry. But yeah, if you're going to go to another planet, you really need that redundancy and resilience that nuclear energy can bring us. Can bring us.

0:35:57 - Tariq Malik

So we were just talking offline. That reminded me that the Titan helicopter drone that NASA's planning is also going to be RTG Dragonfly. So I was just mentioning it to Rod, but we don't know if they're going to survive.

0:36:10 - Dr. Robert O'Brien

Yeah, right Well so far yeah yeah, I hope so.

0:36:14 - Rod Pyle

Yeah, all right, we're going to go to one more break and we'll be right back. Stand by. So when you're talking about mass trades, I guess, or however that's addressed is there a point you know for the kind of power you're talking about in the megawatts, is there a point at which you really need to go to something like a fission reactor as opposed to an RTG, or can you just keep scaling RTGs?

0:36:40 - Dr. Robert O'Brien

Well opposed to an RTG, or can you just keep scaling RTGs? Well, if the world had an abundance of the isotope materials of choice, isotopic materials like americium, plutonium, and we had an abundance of it, or even curium, then you know we we could build systems that are in the multi kilowatts it's. It starts to break even from a power density perspective, though in that kilowatt range. So that's where reactors start to become a really favorable system when you need kilowatts. So when we're talking about human expeditions, you could think of an RTG as a really essential lifeline or a backup battery that's always going to be on, it's always going to be there ready. But you need fission to generate the high power use cases for those high power budgets, but for small systems.

This is where isotope power really opens up what can be done. In fact, I got a little desk toy here. This is our AMBA system that we're developing. This is a CubeSat scale. So this is a mock-up of our americium-powered CubeSat system. Wow, it kind of turns everything upside down. So this is the scale that really can be enabled for the outer planets if you use RTGs. And this is the scale that it really opens up because you can start to look at commercial and semi-commercial isotope supply chains that give us access to these missions and then will enable science to be done in the darkest and coolest places of the solar system and beyond, and I think that's really where it's interesting for, for people who are just listening, rob was holding like a little mock-up of a cube set.

0:38:22 - Tariq Malik

That is about the size of a rubik's cube.

0:38:24 - Rod Pyle

From what I can tell, a little bit bigger than a little bit bigger yeah but that's that's one to one right, one to one scale this is one to one.

0:38:31 - Tariq Malik

Yeah, so this is what we would consider a three, a three cube set yeah it looks like a big coffee coffee mug with a bit of a space in between. And then the RTG looks like the size of a duck roll tape, like a great big jumbo one on the back. That's pretty cool, that's pretty slick. Well, I guess, just to add to that, I recall several years back a whole big hullabaloo with why NASAa didn't have any missions planned, uh to use rtgs going out, because because we didn't have any uh nuclear material to make them uh out of. And and then the, the, the department of energy, they, they worked together, they were able to restart a pipeline to make uh, uh to make that stuff. So so it sounds like the reason that you and I don't have RTG refrigerators or the house, like the world of Fallout or the Atomic Age promised us, is because this stuff is just so hard to come by.

And I'm just kind of curious are we out of it of the plutonium and all that stuff already, or do we have to just keep making them in the reactors? Is there not a factory that can make this stuff for space exploration, that then we can build probes to our heart's content?

0:39:46 - Dr. Robert O'Brien

You know that's a complex question, Tariq. I'll try and explain an answer to it. We became internationally dependent on our supply chain through the 90s, after the fall of the Soviet Union. We worked closely with the Russian Federation. The supply chain that we became comfortable with came from the Russian Federation for plutonium-238.

Now that is an isotope of choice because it's about a half watt per gram. So not only is it a long enough life to actually build a battery, you can put it in the vault, you can store it until the mission is ready. If you scrub a mission window, you can wait for the next one to open up for Mars or other launch windows. So it's a great isotope. It's actually one of those isotopes that we moved away from polonium-210. That was an isotope that was looked at, that was what was taken to Eisenhower's desk in the 50s and that has its challenges because that's only a 110-day half-life. So plutonium-238 is in the sweet spot of isotopes. It's a decent power density half watt per gram, and it has an 88-year lifetime or half-life, and so it's a great isotope.

The challenge with it is it has to be produced in nuclear reactors. We had a moratorium on separation technology and reprocessing of spent fuel and what I would say is lightly used fuel where you go to 3%, maybe 6%, burn up in some cases of nuclear fuel. There's a lot of unused fuel there that if we could reprocess it we could put that back into the commercial fuel cycle. And, by the way, you can take parts of that waste stream and use it to power CubeSats like this that waste stream and use it to power CubeSats like this or systems like we do on the flagship scale with plutonium-238. One of the other challenges why this is complex is in the 90s we shuttered five production reactors at Savannah River National Lab and the five production reactors up in Hanford, and we did that because the world was changing from a geopolitical perspective and we have a need for medical isotopes.

We have a need for isotopes for RTGs and deep space, but we quite frankly don't have production reactors anymore. We have test reactors. These are great to make what the name would suggest, research quantities, and so some of the challenges that the Department of Energy has faced over the last few years is to address the mission and the need of the nation to make plutonium-238, but without the tools in the pouch to do it. You really need a production reactor, or you need to be able to produce material in reactors that have the neutron economy, the fuel cycle length that actually matches the best place and the sweet spot in the production curves.

Actually, at the Center for Space Research, we started looking at this problem probably about 15 years ago, when the crisis started to percolate, where supply chain from the Russian Federation started to be challenged from their perspective changes, and so we have to look at other solutions today that are, you know, outside the box thinking and use the tools that we have access today. But the resistance to change is really tough, and so, because of that, we've seen a few grams per year produced after tens and tens of millions of dollars are spent on production. Only a few grams is very, very short of a one and a half kilogram a year production rate target. So there are capabilities on the full life cycle.

We've got supply of target material in the nation. We can do that, but what we're missing is that one tool. So, as we look at advanced reactor developers that are working today, there's certainly an outlet there for their technologies to align with isotope production and some of the IP that we looked at as very novel target technology. So looking at not just the traditional approach to putting a solid material into a core and irradiating it, but looking at optimizing the number of days that that material stays resident in the reactor and pulling it out at the right moment in time so that we don't burn more material than we produce. It's a really real tough neutron economy, physics, chemistry problem set that we have and I think there's paths forward if we can think outside the box, change the status quo and align with new technologies in reactors as well as new target technologies.

0:44:44 - Rod Pyle

I never realized that making plutonium is so much like baking cookies or croissants that's kind of interesting that you have to know when to pull them out of the oven. We're going to jump to one more break and then I'm going to come back with my next question, so stay with us. So you mentioned plutonium 238 being the kind of the sweet spot, but if you're going for really extended missions, if I got my research notes correct, americium has a half-life of 432 years, which is it just lower energy density per unit of mass or something?

0:45:20 - Dr. Robert O'Brien

Yes, it's about one fifth the energy density of plutonium-238. And that's that trade space that you've got to look at from an engineering perspective. Can you tolerate less heat generation but know that you have much more resilience and lifetime because of it? And I became a believer in americium as a PhD student when I was scouring the chart of the nuclides, and half of my thesis is the discovery of americium for RTGs being a good option, certainly for Europe and, as we face this crisis, for plutonium production here in the US. I think it presents a very, very sensible approach to powering commercial missions and also powering US government missions.

0:46:10 - Rod Pyle

Is americium easier to make in some way?

0:46:13 - Dr. Robert O'Brien

There's an abundance of americium in the fuel cycle. That's what's different. It is a fission product from the fuel cycle, so it doesn't require new irradiations, it requires just separations. And while that was verboten up until this year, what's very exciting about the new executive orders that were just signed, just a month ago? It opens the door, lifts the moratorium on reprocessing. This has been a you know, it's been a pair of handcuffs for the nation that we needed to remove because, you know, we need to power this nation, we need to power our missions in space, and the only way to do that is to free the material that is locked up in dry storage across the nation and let's get it out and start using it.

0:47:00 - Tariq Malik

It doesn't hurt that its name is Amerisium, right it?

0:47:03 - Dr. Robert O'Brien

doesn't.

0:47:05 - Tariq Malik

Did I make my pronouncing that right Amerisium?

0:47:08 - Dr. Robert O'Brien

Amerisium yeah.

0:47:09 - Tariq Malik

Amerisium which is named after the Americas, right?

0:47:14 - Rod Pyle

So it's like ah, that's my eagle sound, so I guess my question is is separating americium from other nuclear products, something I can get a contract to do in my backyard, or do you have to have a somewhat more sophisticated setup?

0:47:28 - Tariq Malik

Can I, can I ask a follow up for the same for this, because it seems like you can just build this into a commercial reactor business model and say we're gonna give you guys some power and, by the way, we've got this extra stuff that we can sell back to the government to launch missions to, you know, neptune, right? So I guess that's a two part question.

0:47:48 - Dr. Robert O'Brien

Yeah, I think the important thing to remember about americium is it's been in all of our homes for the last few decades. If you've got a smoke detector, some of the early smoke detectors had americium foils in them and the way they worked was they fired their little alpha particle from one side of the foil to a detector or a collector and if smoke got in the way, it disrupted the flow of those alpha particles and the sensor would trip and then you had that piercing sound. So we're all used to using americium sensibly and it can be safely operated, and even in the home. And so, yeah, we know how to do it, we know how to use it.

The supply chain is there. There's a lot of americium in spent fuel stores and absolutely there is a commercial supply chain that exists today that can be brought to bear and accelerated. And I think that's what's exciting is that we're on the cusp of a demand signal driving a commercial boom. No pun intended, because we absolutely want to avoid a boom, but we want to see a business boom. And that's where the commercial world can now come and help the US government, help commercial missions in space really solve some of the toughest challenges for the environments we operate in.

0:49:10 - Tariq Malik

So we don't want to send some Boy Scouts house to house trying to collect old fire detectors, right Of course you probably know about the atomic Boy Scout, right, Tariq?

0:49:18 - Dr. Robert O'Brien

So, yeah, so that poor soul did indeed try and separate and dissolve smoke detector foils and yeah, it's that simple, he crudely dissolved-.

0:49:31 - Tariq Malik

I was making a joke that really happened. Is that what you're saying?

0:49:36 - Dr. Robert O'Brien

Yeah, so go Google the At Google the, the atomic boy scout, Poor gentleman, you know, learned the hard way about the hazards with working with nuclear materials.

So americium is you know, it deserves the respect, absolutely it deserves, deserves the respect that it needs because you know it does produce a soft gamma ray, it produces neutrons, it's an alpha particle. So if it's on the skin, in the lungs, it can cause damage. So we have to mitigate the health hazards of operating that material, working with that material, reforming it. But yeah, the Atomic Boy Scout discovered that you could dissolve the smoke detector foils and he was using precipitation techniques to make americium oxide in coffee filters. Oh my gosh.

0:50:27 - Tariq Malik

Yeah. So for people who I mean, this is news to me, and I'm an Eagle Scout. You'd think I would know about this story, but this was an Eagle Scout. Oh man, my age oh my gosh David Hahn. Wow, that is crazy Smart guy yeah, very smart In his mom's shed to make a breeder reactor.

0:50:47 - Dr. Robert O'Brien

Wow, that's why I think what we're doing with the workforce development at the center and as we're looking at the future if people are curious, give people the center or the place to be curious, but be curious safely so that they can make discovery, and they've got expertise around them to guide them on that journey. And I think that's what's exciting right now is seeing the demand there, Darrell.

0:51:14 - Rod Pyle

Bock. Well, and it's so interesting when you look at public perception. So, as I mentioned earlier, when I was a kid you know it was the Adams for Peace era and all that. In 1954, gilbert Toys Science Toys put out the Gilbert U-238 Atomic Energy Laboratory kit, which was a little briefcase-sized thing. It had a cloud chamber, it had various other little experiments with chemistry you could do, but it also had radioactive elements and that included I was just looking at it here plutonium-210, ruthenium 106 and zinc 65.

So I presume these aren't like hold it in your hand and you know it burns through it kind of elements, but they're probably still not the best thing to give kids who are going to eat them and inhale them and things like that.

So you know, here's the beginning of kind of a bad name and in the public eye for for atomic toys, if you will. But then, as you mentioned when we were talking before the show, you get into the 60s with Earth Day and into the 70s with more environmental concerns and suddenly this idea of wait a minute, you're going to put nuclear material on a spaceship that might crash or blow up, and I think the public got very worked up about that when in reality, at least on the NASA side, there was tons of work put into these. I think they were ceramic casks that they put the elements in and so forth. And at least once on our side, and a number of times on the Soviet side, things did reenter and crash in the ocean and so forth, but so far as I know there hasn't been any recorded fallout, if you will, from that.

0:53:05 - Dr. Robert O'Brien

Is that correct? That's right. So when we talk about the engineering solution, I'll show this widget again. But a lot of the packaging for isotopes we design so that they can survive even the worst case scenarios for launch-related accidents. So that often relates to using an ablative structure, an impact shell, so that it can hit the surface tension of water, hit the land and we can retrieve those sources. Back in the early days, when we were discovering the health effects of radionuclides, some of the early strategy for launch accidents involved dispersion in the upper atmosphere and the theory was the solution to pollution was dilution. That's probably not a good strategy for everything, especially long-lived isotopes like Amory.

C-241, plutonium. Yeah, it's something that we have to engineer and provide protection. So the design of these systems is such that everything the cladding around the fuel itself, even the pellet itself, can be engineered to be more resistant. At the center, and with our industry partners, we're working on some new compounds that are even safer than the oxides that were used before. These are borides. These are materials that are water resistant, provide protection if seawater is around it. They're impact resistant. You can't cut them easily. They're very hard materials. We're building the design and now we're getting ready to develop the materials properties, libraries of how to use them and complete the design lifecycle. So I think this is using what we know is the right strategy for protection and thinking through the next generation.

0:54:54 - Tariq Malik

Do we? You know there doesn't seem to be a lot of missions on the drawing board that are official, for that would require larger RTGs in the future. But, aside from the CubeSat concept that you're developing, what would be, I guess, your dream mission that would be powered by RTGs either in our solar system or beyond, given, I guess the half-life by RTGs, either in our solar system or beyond, given, I guess the half-life I mean 88 years doesn't sound like enough to get to Alpha Centauri, but I'm just curious how far they could go.

0:55:25 - Dr. Robert O'Brien

Well, I think seeing a CubeSat this size go out of the solar system, that would be a dream mission. Being able to get data from the Kuiper Belt and beyond, you know, an interstellar fleet of CubeSats, I think would be pretty cool. But even closer to home, exploring Shackleton Crater. I was part of the Lunar Beagle team back in the early 2000s in the UK and we were looking at an americium-powered system then to power a mission to get into the dark depths of Shackleton Crater on the moon.

0:55:59 - Tariq Malik

Well, I'm still sad I don't have my atomic car. I guess I will err on the side of safety after the cautionary tale that I just learned about for the first time today.

0:56:10 - Rod Pyle

Well, if you've got a couple thousand dollars, you could buy one of those Gilbert Atomic Labs.

I just want to touch one more time on the safety question because I think, at least if you've read much about this kind of thing of thing another black eye that, uh that both fission reactors and rtgs have gotten is from the soviet union, who, uh, deployed like over a thousand of these things all over the world. So if they were the arctic or the antarctic or undersea or somewhere where it's difficult to change batteries or refuel things, they just stuck some plutonium there with some thermocouples wrapped around it and said have a good life and walked off. And then when the soviet union fell, I guess a lot of them got left behind. Some were actually pried apart by people trying to salvage the metals and so forth, with predictably poor results. So that was not handled well and as far as I know, a number of them are still, if not unaccounted for, at least not scavenged. On the American side and in the West in general it's been a much more careful process instead of deployment, recovery and curation right.

0:57:19 - Dr. Robert O'Brien

Absolutely. Source recovery is an important mission for the Department of Energy, NNSA specifically, and industry partners that go around the country and around the world retrieving everything from medical sources to old sources like you're talking about. That's really important that we do that.

0:57:39 - Tariq Malik

What about ones in space, though, because I recall that they were used for a lot of orbital stuff too, with the military and whatnot. That I mean, those would be up in a graveyard orbit still doing their thing. We couldn't salvage those, maybe, or, or we could.

0:57:54 - Dr. Robert O'Brien

I I think uh the the dawn of uh service missions service retrieval missions is is going to change everything we saw last week uh China successfully did a propellant transfer demonstration. I think we're going to see more demonstrations like that that talk about going and restarting graveyard-based assets.

0:58:17 - Rod Pyle

So I think watch this space. So can we foresee a book from you sometime in the future about nukes in space or something?

0:58:28 - Tariq Malik

Another book. It's got to be Another one.

0:58:30 - Rod Pyle

Yeah, it's got to be a catchy title, because publishers love catchy titles. I wrote one years ago called Amazing Stories of the Space Age and the subtitle started with Nazis in Orbit, and the publisher actually called me when we were about to go to press. No, after it had been on sale for six months, he said okay, from now on, all your books have to have Nazis in the subtitles, because that sold really well, or Nazis in Space or something which I wouldn't recommend for you. But is there a book in this, you think?

0:58:58 - Dr. Robert O'Brien

I think there's a book inside. Everybody that works in this field that's what I will say, and I have an idea for a book right now. I've been working on fueling the nuclear rocket for the last 15, 20 years, working on RTG technologies like americium. I think there's probably a book title, something like that Fueling the Nuclear Rocket Maybe a cool title, but we're looking at everything from solid state to different states of matter that we can cover in that book, so I think it could be interesting. Yeah, yeah.

0:59:34 - Rod Pyle

I guess my last question, if I may, is a little bit of a departure, but I just was reading the other day that DARPA has shut down the nuclear thermal propulsion program they were going to be working on. I think it was called Draco, am I remembering correctly?

0:59:51 - Tariq Malik

Yeah, that's correct, the Draco.

0:59:53 - Rod Pyle

So is that to focus instead on nuclear electric, or are we just backing away again?

1:00:00 - Dr. Robert O'Brien

I think it's really important to address that elephant in the room. That was not a technical decision to cancel the DARPA part of the partnership with NASA. It was purely program management. There were some challenges on program management, project management and I think, from the perspective that I have, I think there's no technical showstoppers for nuclear thermal propulsion. In fact, we must continue to invest and invest our time and efforts in developing nuclear thermal propulsion If we're going to stay a preeminent nation in space exploration but most important space operations when we think about national security, we need propulsion and power.

The two go hand in hand and advanced technologies that we're working on with our industry partners are looking at hybrid systems, so it doesn't have to be one or the other. The parochialism needs to stop. We need to work in our great swim lanes that we all have and start pulling together for our nation, or we're going to start and see more Sputnik moments like on-orbit refueling, which is a serious deal. We've still got to demonstrate that for Starship to be successful from a commercial perspective and for us to go to Mars, this is not the time to give up. This is the time to invest. There are great minds in lots of really unique and capable places, both in commercial and in government. We need to keep the alignment, keep the progress moving forward and it's great to see that there's a glimmer of hope with the Senate and House working to keep the momentum moving forward. On propulsion, they recognize the importance of propulsion with nuclear power and it's all three nuclear, electric, nuclear, thermal and high power that is needed for us to enable our national missions.

1:01:58 - Rod Pyle

Very well said and, as you kind of alluded to at the end there, it's not just getting these places but it's surviving and powering something meaningful once we're there. And I'm kind of the raging nationalist on the show, I guess, although I'm not really, but compared to Tariq I am. But you know, china's not slowing down and although we've kind of kissed up to and backed away from nuclear propulsion numerous times after kind of proving at least that nuclear thermal could work back in the 60s and 70s, china's working on it full speed ahead. They don't have budget shifts every year, they don't have these shortfalls at least not from what I've read and you know we're very soon going to be seeing our lunch being eaten by this other power. And you know, maybe that's okay, I mean, maybe it's all right if they become dominant in space.

We kind of moved down to second round because we feel like we've done it already. But personally I don't think it's okay and I like the fact that NASA has been a leader in this and the DARPA has been a leader in this, that the West has done so safely and responsibly, and I'd kind of like to see it continue to move ahead. And it's really a head scratcher sitting in the peanut gallery as to, because I, you know, I read about the politics from a distance, but I certainly don't have the inside view you do as to how these things keep torquing and twisting and up and down. And maybe we will, maybe we won't. I don't want to do it this year, maybe we'll do it next year. They won't wait forever. We now have a competitor, a very keen competitor, not just one either, rod.

1:03:26 - Dr. Robert O'Brien

We've got a coalition, a global coalition that's growing. Russia and China are cooperating on nuclear power for space. This week we see that the Zeus concept has been apparently tested, probably in a ground test configuration in the Russian Federation. So we know that Russia and China are cooperating on a lunar solution as well. So lunar power, fission, surface power.

So international lunar research part. That's right. That's right, exactly. So now is not the time to give up as a nation. We must must keep pushing forward. Yeah, I think. I think this is enabling technology in more ways than one, and the ramifications of giving up and complacency of historical capabilities I think is a very dangerous one. We must keep pushing forward on the research, the technology development and the commercial side of development and deployment.

1:04:29 - Rod Pyle

Okay, Tariq, we've got to figure out a way to digest that onto a T-shirt.

1:04:33 - Tariq Malik

I know I was going to say just wait for the congressional hearing. Someone's going to say something and start poking some wasp nests, you know, to get some stuff going.

1:04:43 - Rod Pyle

Well, hopefully they'll ask Rob instead of us. I want to thank everybody very much for joining us today for episode number 170, that we like to call Atomic Space Batteries, and thanks once again to the University Space Research Association, who has kindly provided us a number of guests, all of whom have been superior, and you're right there at the top, rob. So thanks very much. Is cs.ucr.edu still the best place to keep track of the advancements?

1:05:12 - Dr. Robert O'Brien

Good, place to keep track and watch us on LinkedIn. We like to share what we can on LinkedIn and, yeah, happy to engage. Anybody that's interested reach out. Happy to work with you, thank you.

1:05:24 - Rod Pyle

Fantastic, Tariq. Where can we find you recharging your atomic batteries?

1:05:28 - Tariq Malik

well, you can find me at space.com, as always on the twitter and the blue sky and instagram, all that stuff. At Tariq j malik, uh, this weekend, you'll see me at the rocket launch, uh on saturday, uh the 26th, uh in fortnight. It's very exciting and then and then going to go see fantastic four, because I heard there's a rocket launch in there too, spoiler alert. I've seen it. It's amazing, so everyone should check it out.

1:05:52 - Rod Pyle

Okay, just a reminder the stuff that happens at Fortnite isn't real, you know that right?

1:05:57 - Tariq Malik

Hey, I'm not going to space anytime soon. Rod, this is like the next best thing I can do.

1:06:02 - Rod Pyle

Well good point. Neither am I. And Well good point, neither am I. And, of course, you can find me at pylebooks.com or at adastramagazine.com the soon to be revamped. At adastramagazine.com, because we've got things in the work there to expand our footprint dramatically. And remember you can always drop us a line at twis@twit.tv, that's T-W-I-S@twit.tv

We welcome your comments, suggestions and ideas and one of us usually me will answer everything that we get new episodes, this podcast published every Friday on your favorite podcatcher and elsewhere. So make sure to subscribe, tell your friends and give us lots of good reviews. I mean, it's not like you can't give us bad reviews, but we'd rather you didn't, because we need the love. You can also head to our website at twittv slash twis, and please don't forget, we are counting on you. No, we're dropping to our website at twit.tv/twis and, please don't forget, we are counting on you. No, we're dropping to our knees and begging that you join Club Twit in 2025.

As you know, if you listen to the other shows of this network, advertising revenue doesn't cover the costs and God knows if there's too much of a shortfall. I don't know, Tariq, maybe we're first on the chopping block. I wouldn't want to be. No. No, because we really enjoy doing this. So join Club Twit. It's only $10 a month. You get access to all the shows in both audio and video material that you can't find anywhere else. You get to join us on Discord and leave snarky comments that we respond to on the air and all kinds of other stuff, and it's just a great bargain for a great network. So sign up. Finally, you can follow the Twit Tech podcast network at Twit on Twitter and on Facebook and twit.tv on Instagram. Thank you very much, rob, and thanks everybody for listening, and we'll see you soon next week.

1:07:41 - Leo Laporte

No matter how much spare time you have, twit.tv has the perfect tech news format for your schedule. Stay up to date with everything happening in tech and get tech news your way with twittv. Start your week with this Week in Tech for an in-depth, comprehensive dive into the top stories every week and for a midweek boost, Tech News Weekly brings you concise, quick updates with the journalists breaking the news. Whether you need just the nuts and bolts or want the full analysis, stay informed with twit.tv's perfect pairing of tech news programs.