The Zero-Day Arms Race: How America and China Are Competing for Cyber Supremacy

AI-created, human-edited.

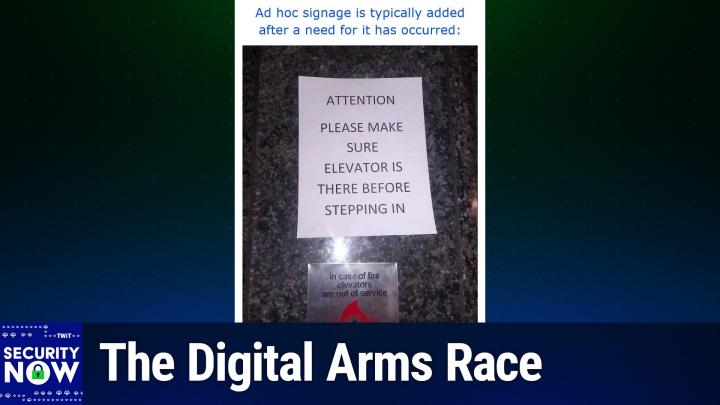

In a recent episode of Security Now, hosts Steve Gibson and Leo Laporte dove deep into one of the most critical and underexplored aspects of modern cybersecurity: the global competition for offensive cyber capabilities, particularly zero-day exploits. Their discussion, centered around a comprehensive report by former Google TAG security engineer Winona DeSambre-Burnson, reveals a stark reality about America's position in the cyber arms race.

Gibson opened the discussion with a sobering observation that has long troubled cybersecurity professionals: while we constantly hear about Chinese intrusions into US networks, we rarely get visibility into American cyber operations against China. This asymmetry in reporting raises fundamental questions about whether the United States is truly holding its own in cyberspace.

"What I wonder is whether similarly cyber-aware Chinese citizens located in China are covering the same sorts of stories about intrusions, plotting and planning being made by the US," Gibson mused, highlighting the inherent bias in how we perceive the cyber battlefield.

The hosts explored the explosive growth of what's become a billion-dollar international services industry built around finding and selling zero-day exploits. These are previously unknown vulnerabilities in software or hardware that can be weaponized before vendors have had "zero days" to fix them.

The scale of this market is staggering. According to the report, Google found that around 50% of zero-day exploits detected in 2023 and 2024 were directly attributable to commercial vendors selling capabilities to government customers. Companies like Israel's NSO Group have reached valuations of $1 billion at their peak.

One of the most concerning revelations from the discussion was the structural advantages China enjoys in this cyber arms race:

While the US military's traditional procurement processes favor large prime contractors and emphasize extremely high levels of accuracy and trust, China uses decentralized contracting methods that are faster and more efficient. As Gibson noted, "China's acquisition processes use decentralized contracting methods... shortens contract cycles and prolongs the life of an exploit."

China's offensive cyber industry is already heavily integrated with artificial intelligence institutions, while the US appears to be playing catch-up in this crucial area.

Perhaps most troubling, China's domestic cyber pipeline "dwarfs that of the United States," while America relies heavily on international talent for its zero-day capabilities.

Both hosts were particularly struck by the inefficiency of the current US system. A senior DOD official quoted in the report called the system "horrendously inefficient and broken," noting that middlemen who contribute nothing beyond government connections can mark up exploits by 7-10 times their original value.

"An individual researcher who is not informed on what bugs are selling for may sell a good bug for $100,000. By the time it makes it to a customer, an individual bug could go for $750,000 to $1 million," the report revealed.

The discussion touched on the complex relationship between the US government and the hacking community. Gibson reminded listeners of the historical tension, referencing past incidents where hackers were treated as criminals rather than innovators. This anti-government sentiment, while understandable given past overreach, now poses a national security challenge.

Leo Laporte referenced the famous scene from "Good Will Hunting" where Matt Damon's character rejects an NSA recruitment pitch, illustrating the cultural resistance many talented hackers feel toward government work.

The hosts explored the challenging economics facing exploit developers. Creating a zero-day exploit can require 6-18 months of full-time work, creating a "feast or famine" cycle that makes it difficult for researchers to maintain steady operations. This uncertainty, combined with the difficulty of finding legitimate government buyers, pushes many talented researchers toward middlemen or away from the field entirely.

Gibson concluded with a stark assessment: the US needs to fundamentally restructure its approach to cyber warfare acquisition. His recommendations echoed those in the report:

- Direct Government Procurement: The US must become a well-advertised, high-value buyer of zero-day exploits

- Legal Protection: Provide irrevocable protection to hackers against blowback

- Eliminate Middlemen: Create direct channels between researchers and government buyers

- Increase Incentives: Make it widely known that researchers can become wealthy selling to Uncle Sam

"This is not the world I wish we had, but it's today's reality," Gibson observed. "If having a strong deterrent helps to keep the peace, then let's get one."

Laporte's final point resonated strongly: while there may be reluctance to escalate cyber warfare, the escalation is happening with or without US participation. The question isn't whether to engage, but whether America will be competitive when it does.

The Trump administration's plans for a "US Cyber Command 2.0" and increased willingness to work with private sector partners suggest recognition of these challenges. However, the window for maintaining cyber superiority may be closing rapidly.

As the hosts made clear, the future of national security increasingly depends on who can most effectively harness the global community of hackers and security researchers. In this high-stakes competition, America's traditional advantages in military spending and technology may not be enough to overcome China's more agile and integrated approach to cyber warfare.