How Mariner 4 Changed Space Exploration 60 Years Ago

AI-generated, human-edited.

When we think of the incredible achievements of space exploration—Voyager's journey beyond our solar system, the Mars rovers traversing alien landscapes, or the Cassini mission's spectacular dive into Saturn—we often focus on the dramatic discoveries and breathtaking images. But behind these missions lies a remarkable technology that has quietly enabled some of humanity's greatest adventures in space: radioisotope thermoelectric generators, or RTGs.

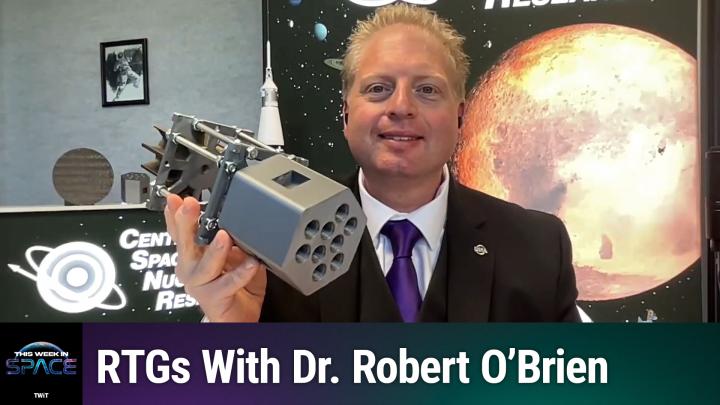

Dr. Robert O'Brien, Director of the Center for Space Nuclear Research at the University Space Research Association (USRA), recently joined hosts Rod Pyle and Tariq Malik on This Week in Space to discuss these "atomic space batteries" that have been powering spacecraft for over six decades. As O'Brien explained, "We've been really pushing the envelope and challenging the bounds of status quo, thinking outside the box, encouraging the next generation of nuclear scientists and engineers into the aerospace crossroads with nuclear energy for that 20-year period."

What Exactly Is an RTG?

Despite being called "atomic space batteries," RTGs aren't actually batteries at all—they're power generators. "An RTG stands for radioisotope thermoelectric generator, and in that name it suggests that what we're converting is thermal energy, heat to electrical power," O'Brien explained during the podcast. The technology works through the Seebeck effect, where temperature differences between materials generate electricity.

The process is elegantly simple yet remarkably effective. Nuclear decay from radioactive isotopes generates heat, which flows through thermoelectric materials to create electrical power. The waste heat is then radiated away to space, just like a car radiator. "It's just that conversion of decay heat, of a radioisotope to electricity through thermoelectric," O'Brien noted.

This conversion isn't perfectly efficient—current RTGs operate at around 30% efficiency, well below the theoretical maximum of 60% dictated by thermodynamic principles. However, their reliability and longevity more than compensate for this limitation.

A Technology Born in the Space Age

The history of RTGs in space exploration stretches back to the very dawn of the space age. The first space-based demonstration occurred under President Eisenhower, when engineers placed a polonium-210 powered RTG directly on the president's desk in the White House—a demonstration that O'Brien called "incredible" and noted showed "trust in engineering and chemistry and physics."

The first operational space RTG flew on the US Navy's Transit 4A satellite in 1961, generating just 2.7 watts of power. While modest by today's standards, this pioneering system demonstrated the viability of nuclear power in space. From there, RTGs found their calling in the most challenging missions, as O'Brien explained: "We wanted to do challenging things, go to challenging places and orbits that might eclipse significantly or have an extended period of time in darkness, and that's really hard to do with solar power."

The Voyager Legacy

Perhaps no mission better demonstrates the incredible longevity of RTG technology than the Voyager program. Launched in 1977 and 1978, both Voyager spacecraft continue operating today, nearly five decades later, powered by their original RTGs. This extraordinary lifespan is possible because of plutonium-238's 88-year half-life, meaning the fuel produces roughly half its original thermal power every 88 years.

"We've still got plenty of life left in the fuel," O'Brien noted, though he acknowledged that other components face challenges over time. "There are other material problems that start to arise with radiation damage. Neutron exposure, gamma exposure starts to degrade the thermoelectrics."

The Voyager mission exemplifies what O'Brien calls "mission enabling value"—scenarios where nuclear power makes missions possible that simply couldn't be accomplished any other way. This principle extends to many of NASA's most celebrated achievements, from the Viking Mars landers in 1976 to the current Curiosity and Perseverance rovers exploring the Red Planet today.

The Supply Chain Challenge

One of the most significant challenges facing RTG technology isn't technical—it's supply chain related. The United States became dependent on Russia for plutonium-238 after shuttering domestic production facilities following the Cold War. As O'Brien explained, "We shuttered five production reactors at Savannah River National Lab and the five production reactors up in Hanford, and we did that because the world was changing from a geopolitical perspective."

This dependency created a crisis that peaked in the 2000s and 2010s when the Russian supply became unreliable. The Department of Energy has worked to restart domestic production, but the results have been modest—"only a few grams per year produced after tens and tens of millions of dollars are spent on production," according to O'Brien, far short of the 1.5 kilogram annual production target.

Enter Americium: A New Hope

The supply challenges with plutonium-238 have led researchers like O'Brien to explore alternatives, particularly americium-241. While americium has about one-fifth the energy density of plutonium-238, it offers significant advantages. Most importantly, it has a 432-year half-life and exists abundantly in nuclear waste.

"There's an abundance of americium in the fuel cycle," O'Brien explained. "It is a fission product from the fuel cycle, so it doesn't require new irradiations, it requires just separations." Recent changes in policy have made this more feasible, as O'Brien noted: "What's very exciting about the new executive orders that were just signed, just a month ago, it opens the door, lifts the moratorium on reprocessing."

Interestingly, americium has been in American homes for decades. "If you've got a smoke detector, some of the early smoke detectors had americium foils in them," O'Brien pointed out, demonstrating that the material can be handled safely with proper precautions.

Scaling for the Future

Current RTG technology serves missions requiring hundreds of watts to low kilowatts of power. For larger applications, such as human Mars missions requiring megawatts of power, nuclear fission reactors become more practical. However, RTGs continue to find new applications at smaller scales.

O'Brien demonstrated a CubeSat-scale RTG system during the podcast—about the size of a Rubik's cube—that could enable entirely new classes of missions. "It kind of turns everything upside down," he said. "This is the scale that really can be enabled for the outer planets if you use RTGs... because you can start to look at commercial and semi-commercial isotope supply chains."

These miniaturized nuclear power systems could enable swarms of small spacecraft to explore the outer solar system and beyond, providing data from regions where solar power is completely impractical.

Safety and Environmental Considerations

Public perception of nuclear technology in space has evolved significantly since the optimistic "Atoms for Peace" era of the 1950s. Environmental concerns raised in the 1960s and 1970s led to increased scrutiny of nuclear-powered spacecraft, particularly regarding launch safety.

Modern RTG design addresses these concerns through multiple layers of protection. As O'Brien explained, "A lot of the packaging for isotopes we design so that they can survive even the worst case scenarios for launch-related accidents." This includes ablative structures and impact shells designed to survive crashes and allow recovery of radioactive sources.

Advanced materials research continues to improve safety margins. O'Brien's team is developing new compounds called borides that are "water resistant, provide protection if seawater is around it. They're impact resistant. You can't cut them easily. They're very hard materials."

The Global Competition

The discussion also touched on international competition in nuclear space technology. China and Russia are actively cooperating on nuclear power systems for space applications, including lunar surface power systems. As O'Brien noted, "Russia and China are cooperating on nuclear power for space. This week we see that the Zeus concept has been apparently tested, probably in a ground test configuration in the Russian Federation."

This competition underscores the strategic importance of nuclear space technology. O'Brien emphasized that "now is not the time to give up as a nation. We must must keep pushing forward on the research, the technology development and the commercial side of development and deployment."

Looking to the Stars

As we look toward future space exploration—whether it's establishing permanent bases on Mars, exploring the icy moons of Jupiter and Saturn, or sending probes to nearby star systems—RTG technology will likely play a crucial role. The combination of long life, reliability, and independence from solar radiation makes nuclear power systems uniquely suited for humanity's most ambitious space exploration goals.

The technology that began with a small demonstration on President Eisenhower's desk has evolved into an essential tool for space exploration. As missions become more ambitious and venture further from the Sun, these "atomic space batteries" will continue powering humanity's greatest adventures among the stars.

From the enduring Voyager missions to potential CubeSat swarms exploring the Kuiper Belt, RTGs represent more than just a power source—they're an enabler of human curiosity and our endless drive to explore the cosmos. As O'Brien's work demonstrates, the future of this technology looks brighter than ever, promising to power discoveries we can only imagine today.